Summary: Financial Accounting: International Financial Reporting Standards (Harrison, Horngren, Thomas & Suwardy)

- Chapter 1: The Financial Statement

- Chapter 2: Transaction Analysis

- Chapter 3: Accrual Accounting & Income

- Chapter 4: Internal control & cash

- Chapter 5: Short-Term investements & recievables

- Chapter 6: Inventory & Costs of Goods sold

- Chapter 7: Plant Assets & Intangibles

- Chapter 8: Liabilities

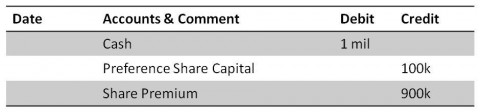

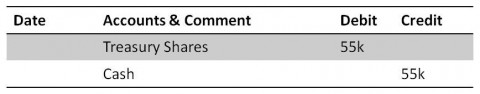

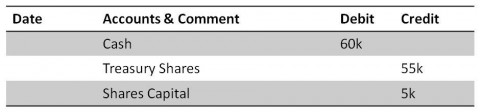

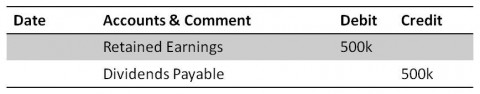

- Chapter 9: Stockholder’s Equity

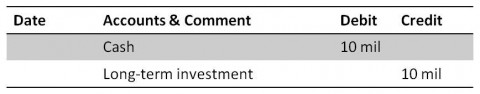

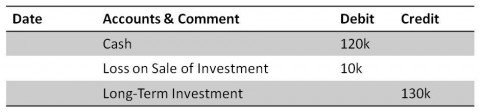

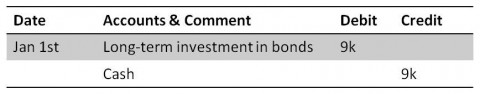

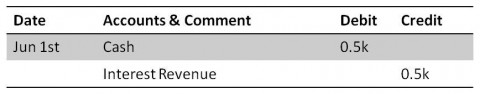

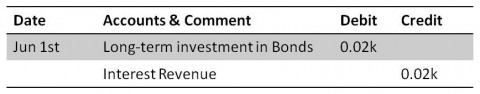

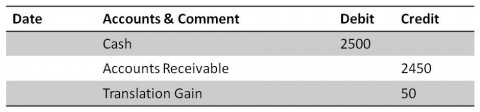

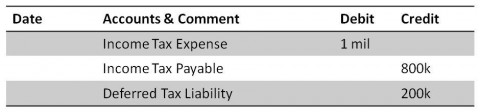

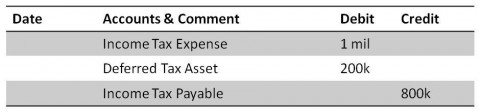

- Chapter 10: Long-Term Investments and International Operations

- Chapter 11: Income Statement and Statement of Change in Equity

- Chapter 12: The Statement of Cash Flows

- Chapter 13: Financial Statement Analysis

- Year of summary

Chapter 1: The Financial Statement

There are two kinds of accounting Financial Accounting and Management Accounting. Financial accounting serves the purpose of informing parties outside of the company. The four main interest groups are: investors, creditors, the government and the general public. On the other hand management accounting gathers and refines information for decision maker within the company, such as the managers. As the name reveals this book focuses solely on financial accounting.

Accounting requires a set of underlying rules and regulations to determine the monetary value that should be assigned to a certain element or transaction. These rules are called accounting standards. Until recently due to different societal development most western countries had their individual accounting standards (referred to as General Accepted Accounting Principles). This made comparison between company extremely cost intensive. Therefore the International Accounting Standard Board was found with the purpose to create internal rules; the result is called International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS). As these standards are adopted by more than 100 countries, this book will only deal with IFRS.

THE CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

IFRS is a principle based accounting standard, meaning that not every individual transaction is described by a rule but rather general principles need to be considered when deciding about how to book a transaction or prepare a statement. The conceptual framework can be divided into five categories, the objective, the qualitative characteristics, the constraints, the assumptions and the main elements of IFRS accounting.

1. Objective of IFRS accounting: “provide information to various user groups that is useful for their economics decision making” (Harrison 2011, page 8). The main groups and their interests are:

a. Investors, do we get adequate return for the risk we take?

b. Employees, are our jobs secure?

c. Creditors, bankers, can we grant additional loans?

d. Supplier, is the company able to pay us?

e. Customers, does the company still exist for necessary transactions in the future?

f. Government, what about taxes, subsidies, environmental and social issues?

2. There are four principal qualitative characteristics that ensure the utility of accounting information

a. Understandability – sufficiently transparent to be understandable for a reasonably expectable skilled and trained person

b. Relevance – the information presented important enough and able to make a difference in the decision making process. The adjective materiality is often used to describe information that is important enough to be listed separately.

c. Reliability – information is reliable if it is complete, free from error and bias and faithfully represents economics substance of the event.

d. Comparability – over time and between different transactions the same principles should be applied to allow unbiased comparability. This is not necessarily the same as uniformity or continuity.

3. Constraints of accounting information

a. Timeliness – it is crucial that accounting information is available as soon as possible; this creates a unavoidable tradeoff between timeliness and accuracy of the information.

b. Balance between the qualitative characteristics – there are many tradeoffs between the four aforementioned qualitative characteristics; the right balance has to be decided from on a case to case basis.

c. Costs/Benefits – the costs of providing information shall never exceed their benefits.

4. Assumptions

a. Accrual Basis – transaction are recognized when they occur, independently of the timing of the cash flow.

b. Going concern – the assumption that the company continues to exist and therefore is able to derive the value from its investments in future periods.

5. Five basic accounting elements of financial statements

a. Assets – economic resources which are expected to produce economic benefits and are controlled by the company (left side of the balance sheet).

b. Liabilities – present obligations which represent the source for the purchase or creation of the assets. They are associated with an outflow of economic benefits (left side of the balance sheet)

c. Equity – the residual when liabilities are deducted from assets. It represents the shareholder claim on the company. Can be subdivided into share capital (investment of the shareholders) and retained earnings (earned by the company).

d. Income – is defined as increase in economics benefit. It can be distinguished between revenue and gain. While revenue occurs only during the normal course of business, gains might not.

e. Expenses – is the opposite of income namely the decrease of economic benefits. Expenses occur in the ordinary course of business while losses may also occur outside of this limitation.

There are three equations which always not to hold within the financial statements:

Balance Sheet

1. Assets = Liabilities + Equity

Balance Sheet | |

Assets | Liabilities |

| Equity |

Sum = | =Sum |

2. Total Revenue – Total Expenses = Net Income (loss)

3. Components of retained earnings:

Retained Earnings (start of period) + Net Income – Paid Dividends = Retain Earnings (end)

FINANCIAL STATEMENTS

There are four different but interconnected financial statements:

- Income Statement (or Statement of Comprehensive Income)

- Statement of Change in Equity

- Balance Sheet

- Statement of Cash Flow

The Income statement lists all operating and non operating revenues and expenses within one period. It always starts with net sales/revenues and end with net income/loss. The table shows an example of an income statement. Expenses and losses are often exhibited in brackets and/or red.

| Income statement | 2011 | 2010 |

| Net Sales | 100 | 80 |

| Other Income | 20 | 20 |

| Total Income | 120 | 100 |

| Cost of Sales | (90) | (80) |

| Gross Margin | 30 | 20 |

| Sales & General Admin | (20) | (12) |

| Depreciation, amortization and provision | (5) | (5) |

| Non-recurring income and expenses | 2 | 0 |

| Earning before interest and taxes (EBIT) | 3 | 3 |

| Finance cost | (1) | (0.5) |

| Income tax | (1) | (1.2) |

| Other Income items | 0.5 | 0 |

| Net income | 1.5 | 1.3 |

The Statement of Change in Equity always starts with the final shareholder equity of the previous period. Then the net income (from the income statement) is added. Although the dividends are payments to the shareholders, they are cash flows out of the company and therefore need to be deducted from the shareholder equity. Finally there can be reclassifications in the value of parts of the equity e.g. due to change in currencies. The final line is the new shareholder equity.

| Shareholder Equity (Dec 2010) | 10 |

| Net Income | 1.5 |

| Dividends | 1 |

| Reclassification | 0 |

| Shareholder Equity (Dec 2011) | 10.5 |

Balance Sheet (Statement of Financial Position) has three main elements Assets, Liabilities and Equity (remember the basic accounting equation). The table shows the typical structure and items of a balance sheet. On the asset side PPE are always long term investments that are expected to deliver economic benefits during their lifespan. The investment expenditures are not accounting for as costs in the period they were created or acquired but rather as depreciation spread over their total lifespan. Intangible assets are different from PPE as they do not exist in physical form. Most common intangibles are patents and brand value. The right side of the balance sheet provides information how the assets where financed. The liabilities are split in short-term (maturity <1 year) and long-term (maturity >1 year). Shareholder equity consists in principle of capital (share value *#of shares) and retained earnings (profits of the firm not paid out as dividends to the shareholders).

| Asset | Liability & Equity |

| Cash | Trade payables |

| Trade recievables | Tax payables |

| Total Current Assets | Short Term Borrowing |

| Property, Plant & Equipment (PPE) | Total Current Liabilities |

| Intangible Assets | Long-Term Borrowing |

| Total Non-Current Assets | Total Non-current liabilities |

| Total liabilities | |

| Shareholder's Equity | |

| Capital | |

| Retained Earnings | |

| Shareholder's Equity | |

| Total Assets | Total liabilities and equity |

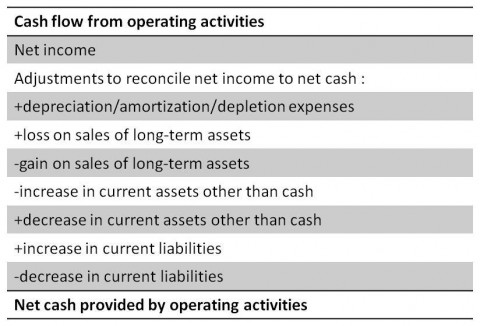

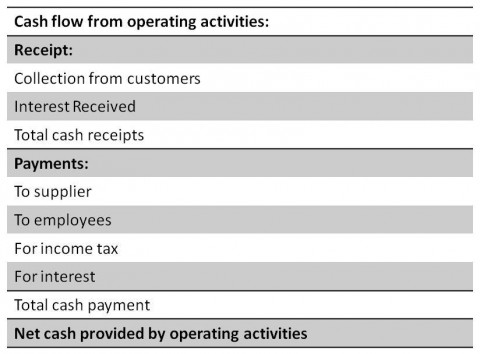

The Statement of Cash Flows provides a testimony about the actual flows of capital that occurred during the period. For example the depreciation of a plant in 2011 is an expense on the income statement in 2011. It will decrease the net income. However if the plant was paid for in cash at the moment it was built (e.g. 2000) then this expense has no underlying cash flow in 2011. Thus the cash flow statement has to adjust the net income for those events. On the other hand if the plant is financed purely by debt and interest + annuity payments were due on a yearly basis, the expense would be synchronous to the cash flow. The table shows a basic statement of cash flow. Hereby a company’s activities are divided into three categories, operating, investing and financing. The element reconciliation is the gap between the accounted income/expenses and the actual cash flows in that period. The final line of the statement is the new level of cash the company has. This is directly translated into the cash position at the beginning of the balance sheet.

| Statement of Cash Flows 2011 | |

| Net Income | 100 |

| Reconcilliation to cash flow from operation | 20 |

| Cash flow from operating activities | 120 |

| Cash flow from investing activities | 10 |

| Cash flow from financing activities | (30) |

| Net Cash flow | 100 |

| Cash at the beginning of the year | 200 |

| Cash at the end of the year | 300 |

As previously said all these four statements are interconnected. To see a visual depiction of this interconnectedness see page 25 of the book. Starting from the income statement, the net income is added to last period’s equity after which the dividends are deducted to derive the new level of equity and the end of the year. This equity flows directly as total shareholder’s equity into the balance sheet. As stated the final cash balance of the statement of cash flows represents the total cash on the left side of the balance sheet.

Chapter 2: Transaction Analysis

In the last chapter we have analyzed the four aggregated accounting statements. During this chapter we go one step back and take a closer look at how accountants process transactions to finally arrive at these statements.

Doubly-Entry Accounting refers to the concept that every transaction has two sides to it, affecting two accounts. For example buying inventory with cash has an effect on the inventory account as well as the cash account. In the following we will analyze this in more detail. Each account can be described as a T-Account (see figure).

| Debit | Credit |

The left side is called debit side while the right side is called credit side. Every individual transaction, such as the purchase of inventory, always involves the debit side of an account as well as the credit side (usually) of another account. The sum of all debit bookings involved with in a single transaction must always be equal to the sum of credit bookings. There are certain rules about T-Accounts you should remember:

1. There are three kind of accounts:

a. Asset, such as cash, inventory, account receivables

b. Liabilities, such as account payables, debt

c. Shareholder’s Equity, such as retained earnings, dividends, expenses and revenues

2. An asset increases with an DEBIT booking in an asset account and decreases with a credit booking in an asset account

3. A liability increases with an CREDIT booking in an liability account and decreases with an debit booking in a liability account

4. Shareholders’ Equity increases with a CREDIT booking in a Shareholder’s Equity account and vice versa. There are two exceptions: Dividends AND Expenses are Shareholder’s Equity accounts but increase with a DEBIT booking and decrease with a CREDIT booking

The following list of common accounts shall provide you with a good overview and a feeling for which accounts can be placed in which of the three categories:

Asset Accounts:

- Cash – back accounts, coins, certificate of deposit

- Accounts Receivable – promise for future collection of cash

- Notes Receivable – similar to accounts receivable but more binding as in written from

- Inventory – everything considered stock in the company

- Prepaid Expenses – as this expense is expected to provide future benefit (by paying for a future expense such as salary) it is an asset

- Property, Plant & Equipment – usually the three are recorded in separate accounts

Liability Accounts

- Accounts Payable – opposite of accounts receivable

- Notes Payable – opposite of notes receivable

- Accrued Liabilities – expenses that have occurred but not yet been paid for

Shareholder’s Equity Account

- Share Capital – owner’s investment

- Revenues – increase in shareholder’s equity

- Expenses – decrease in shareholder’s equity (remember although this is a Shareholder’s Equity account it increases by bookings on the debit side of the account)

- Dividends – cash paid out to the owners (remember although this is a Shareholder’s Equity account it increases by bookings on the debit side of the account)

When reading through this list of accounts one might wonder whether this is simply the same as in the statements described in chapter one. And indeed all these T-Accounts flow eventually into the final Income Statement and Balance Sheet. In the following we will take a closer look at the steps between the T-Account and the final statement. However you should know that a company can have many more individual accounts, than the few mentioned above. For example a company could have a specific expense account for every kind of expense. Yet, this does not change the basic principles described.

As soon as a transaction occurs in a company it is analyzed and recorded in a journal. A journal is simply a chronological collection of all transaction. The figure shows how a journal entry typically looks like. All the journal entries are copied into the ledger. This is simply a summary of all the T-accounts. Unlike the journals the ledger is not sorted chronologically but sorts the transactions by account. Therefore it provides the accountant with information about the total balance in e.g. the Cash account.

The following shows an example of the three different ways to depict a transaction:

1. Journal Entry

| Date | Accounts & Comments | Debit | Credit |

| Jan 1st | Cash - Paid supplier | 100 | |

| Inventory - bought 1000 eggs | 100 |

2. The Ledger Account (after one transaction)

| Cash Account | Inventory | ||

| Debit | Credit | Debit | Credi |

| 100 | 1000 |

3. Accounting Equation

| Change in Asset | = Change in Liabilities | + Change in Equity |

| 100-100 = 0 | = 0 | = 0 |

This case the transaction involves only asset accounts, namely Cash and Inventory. The cash account decreases due to a credit booking of 100 (cash was spent), and the inventory account increases due to a debit booking of 100 (inventory is stocked). These bookings fulfill the set condition that debit and credit need to be in balance.

As it can be inconvenient and in big firms even impossible to always search through all T-accounts in order to get an impression of the financial situation of a company, a trial balance can be created. This trail balance simply lists all the netted balances of each T-account and thereby creates a balance sheet as the shown in chapter one. However it is also important for managers to be familiar with the information hidden in individual T-accounts. For example the Cash account provides indirect information about how much has been paid in cash during each period. By simply adding the opening balance and the receipt cash and comparing it with the ending balance, a manger can easily calculate the amount of money used to pay bills in cash during the period.

There are three rules when searching for errors in an account or balance sheet.

- Always try to go back to the source. Search from the balance sheet – through the ledger – to the journal.

- If there is an out-of-balance amount always divide it by 2 and search for this amount in the transactions. If a transaction has been recorded as a credit instead of an debit it will double the gap between left and right side.

- Still not found? Try dividing it by 9 and search for this amount. If you lost a 0 (such as 50 instead of 500) there will be a miss calculation by 450 (500-50=450). 450/9=50.

These rules will help you find errors more quickly.

As there are thousands of different transactions companies do, there are also thousands of different journal entries.

Chapter 3: Accrual Accounting & Income

In the previous chapter we have learned how the trial balance sheet is constructed. However this trial version has still some significant differences in comparison to the final financial statements. These differences and how we can adjust for them is the main issue of chapter three.

In general accounting can be based on either accrual basis or cash basis.

As mentioned earlier accrual accounting records the economic impact of a transaction as it occurs.

Cash basis accounting records transaction when cash flows occur.

Under IFRS companies need to apply accrual accounting to all statements but the statements of cash flows (see IFRS framework chapter 1). The reason for this is that accrual accounting ensures close connection between records and underlying economic activities.

Accounting on the basis of accrual has an impact on the income statement as well as the balance sheet, thus we have to make adjustments to our trail balance sheet. For these adjustments we have to remember three principles:

- The Time-Period Concept – this principle states that accounting information needs to be recoded regularly, as this is the only way a company can be certain about its financial situation. Under IFRS firms need to publish the records once a year, but many firms do it on a quarterly basis.

- Revenue Recognition Principle – revenues are recognized when they occur NOT when they are paid for. This might be when ownership is transferred or control is passed. For example if Jim agrees with his grandma to clean her windows next week and receives right away €10 for it, Jim should only recognize the €10 revenue once he has provided the service, not the moment he receives the cash.

- The Matching Principle – when recognizing expenses they should be matched with revenues. This works in two steps:

- The total amount of expenses is identified

- The expenses are matched against revenues

Matching costs basically means deducting them from the according revenues to derive the net effect. It is important to keep in mind that an expense can occur from spending cash or using up an asset. If a company has a constant production, employee expenses occur equally during the year. These expenses are only paid for each month or sometimes only at the end of the year (end of year bonus). However the expenses need to be recognized when they occur.

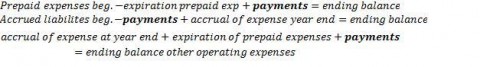

How to adjust

First the following account to not need to be adjusted as they are automatically up-to-date: Cash, Equipment, Accounts Payable, Share Capital and Dividends. All other accounts need to be reviewed. When adjusting it is crucial to always take into consideration WHEN a transaction occurred and WHEN the actual revenues and expenses where realized.

There are two main categories of events we have to adjust for:

- Deferral – the company received or paid cash before any service or product was delivered

- Depreciation is a special case of deferral. In this case the asset involved is always Property, Plant and Equipment.

- Accrual – revenue or expense have been recorded before cash has been paid or received

Deferrals:

Prepaid expenses are expense the company paid for without receiving any benefits therefore they are assets (remember: expected to yield future economic benefits). The most common examples for prepaid expenses are rent and paying in advance for supplies. In the following we will take a look at rent adjustments. For this purpose I will always provide all three formats of exhibiting a transaction: journal entry, ledger and accounting equation.

Rent:

Imagine you rent an office for 100 per month. The owner gave you a really good deal but expects you to pay the full amount for the year on the 1st of January in advance. How to book the 1200 paid for in January, when the whole value is only realized throughout the year.

| Date | Accounts & Comments | Debit | Credit |

| Jan 1st | Prepaid Rent (1 y. in advance) | 1200 | |

| Cash | 1200 |

As explained earlier the prepayment is an asset. The booking on the 1st of Jan should build up the asset Prepaid Rent and reduce the asset Cash (as it was paid in cash)

The T-Account of Prepaid Rent should show 1200 on the debit side. The asset was built up by this amount. The same 1200 can be found on the credit side of the cash account.

| Change in Asset | = Change in Liabilities | + Change in Equity |

| 1200-1200 = 0 | = 0 | = 0 |

| Debit | Credit |

| 1200 |

As the transaction increases one asset and decreases another the total impact on liabilities and equity is zero.

These are all the bookings and transaction on the 1st of January. Now it is 1st of February and we have worked one month in the office. Therefore we should realize expense for 1/12 of the yearly rent. The following bookings take place.

Expense account Rent Expense is built up by 100 (1200/12). As we have already paid the rent, the account is not booked against cash but against the previously build up asset, Prepaid Rent.

| Date | Accounts & Comments | Debit | Credit |

| Feb 1st | Rent Expense | 100 | |

| Cash | 100 |

The T-Account for Prepaid Rent shows a credit booking of 100, while the expense account Rent Expense has the counter booking. This transaction realizes the expenses for renting and using the office for one month (outflow of economic benefits), thus equity decrease as well as the asset Prepaid Rent.

This transaction will be repeated every month until the end of the year. By then the asset Prepaid Rent will show a balance of zero and the account Rent Expenses a balance of 1200. Prepayments for supplies work exactly the same way. Instead of Prepaid Rent the asset Supplies is built up and instead of Rent Expenses the expense account Supply Expenses is used.

Depreciation is a special case of deferrals because it involves a long-term asset. Imagine you buy a large specialized printing machine for your office. It costs 1.2 million and is believed to have a lifetime of 10 years. On January the first when you buy the machine and pay in cash the following booking occurs.

The purchase builds up the asset account Equipment and uses the asset account Cash

- A booking on the debit side of the Equipment account occurs the counter booking is a credit booking on Cash.

- This booking increases and decreases an asset account by 1200. The bottom line change is zero.

When the equipment is used the company should realize an expense (remember: not when it was paid for). There are many ways to calculate or estimate the usage of the equipment over its lifespan. The most commonly used one is called straight line depreciation. Here it assumed that the usage is equally spread out during the lifetime of the equipment. In our case this means: 1200 thousand / 10 years = 120 thousand per year – 120 thousand per year / 12 = 10

Thus the company needs to recognize an expense of 10 thousand per month for using the machine. This is done in the following way:

On February the first we book 10 on the expense account Depreciation Expense and 10 on Accumulated Depreciation. Here we see why depreciation is also a special case. The long-term asset (equipment) receives not credit booking, but an extra account is created to show the accumulated depreciation. This account is a so called contra asset account. This sort of accounts always has companion accounts, in this case the Equipment account). Also, its normal booking is a credit booking, unlike other asset accounts. Recording the transaction like this has two advantages. First it preserves the original purchasing price of the equipment and at the same time it shows the depreciation up-to-date.

The three accounts involved show the following balances:

Equipment

| Debit | Credit |

| 1200 |

Depreciation Expense

| Debit | Credit |

| 10 |

Accumulated Depreciation

| Debit | Credit |

| 10 |

The equity is reduced due to the expense and at the same time the asset side was reduced by the contra asset account Accumulated Expenses.

Unearned Revenues is cash received from a customer before a service or product has been delivered. While prepaid expenses are assets, unearned revenues are a liability as it is expected that economics benefits will flow away from the company in the future, namely in the form of a service. Imagine you sign a contract to deliver a service. You are paid in the beginning of the year in advance and have to perform the service during the course of the year.

- The moment you receive the cash, your cash account increases but also the liability account Unearned Revenue builds up.

- The unearned revenue is a liability account and thus increases with a booking on the credit side.

- This event increases an asset as well as a liability, thus the equity stays unchanged.

At the beginning of the next month the company has delivered the service for one month and should therefore realize the revenues for this service.

- The liability Unearned Revenue is used up and a revenue is recognized on the account Service Revenue (remember: revenues are Shareholder’s Equity accounts and thus increase with a credit booking)

- The balance for Unearned Revenues decreases by 100 due to the debit booking.

- In this case the Equity increases by 100, because revenue has been recognized.

The three examples above are the most common forms of deferral adjustments.

Accruals:

There are accrued expenses, namely those that have occurred but not yet been paid for and accrued revenues, namely if a revenue has occurred but not yet been paid for.

Accrued Expense: Imagine you have hired an employee for your company. The employee is working five days a week but you only pay him at the end of the month for the past period. If the pay day happens to fall on a weekend or national holiday the following bookings occur:

Salary is paid in cash and expense increase.

The T-account shows the increase in expenses

The paying of salary decreases cash as well as shareholder’s equity

As the paid day is a holiday the accounts need to be adjusted.

Instead of booking the expense against cash. It is booked against salary payable as it is accrued (even if it is only over the weekend).

The expense account is increased as well as the liability account Salary Payable.

The accrual increases the liability of the company and thereby decreases the equity.

Accrued Revenue:

If a service is only paid at the end of the month or year but performed during the whole period the providing company can make a accrued booking to adjust for the accrued revenues.

- The asset account Account Payable is build up as a future payment is expected.

- An asset is build up and the shareholder’s equity increases by the same amount.

The moment the cash is transferred accounts payable is booked against the cash account. This transaction is then just asset to asset and does not alter the equity or liability side. On pager 153 in the book you can find a good overview of all the booking codes involved in adjustments.

When including these adjustments into the trail balance we can directly create the final financial statements. Remember to always start with the income statement then the statement of change in equity and finally the balance sheet, as you need the net income to derive the total equity and to finally calculate the shareholder’s equity.

Closing accounts:

After each accounting period certain accounts need to be closed in order to start with a clean balance in the next period. These accounts are called temporary accounts opposed to permanent accounts. Temporary accounts are all revenues, expenses and divided accounts because these events are specific for one period. Permanent accounts are assets, liabilities and shareholder’s equity.

You have to remember three transactions when closing the accounts:

- The revenue accounts increased with credit bookings during the period. Now make a debit booking in each account that balances the whole account to zero. The counter account is retained earnings (credit booking).

- The expense accounts increased with debit bookings during the period. Now make a credit booking in each account that balances the whole account to zero. The counter account is retained earnings (debit booking).

- The dividend account increased with debit bookings when dividends are paid. Now make a credit booking in each account that balances the whole account to zero. The counter account is retained earnings (debit booking).

After these transactions the retained earning account should have all expenses and dividends paid out on the debit side and all the earned revenues on the credit side. The balance shows how much retained earnings the company achieved during the period.Classifying assets/liabilities:

IFRS requires that assets and liabilities are classified in the balance sheet by their liquidity. Most commonly the balance sheets starts with the most liquid assets/liabilities, however this is not standardized. In descending order:

1. Current assets/liabilities

a. Cash, account receivables, inventory etc.

2. Non-current assets/liabilities

a. Long-term investments (PPE), intangibles

While besides this there is no standard format how the balance sheet needs to look like there are two formats for the income statement. You can report the expenses in the income statement by one of the two ways:

- by nature of expense – employee costs, transportation costs, material costs etc.

- by the function of expense – production costs, marketing and sales costs, admin.

The second form is more commonly used.

Account Ratios:

- Current Ratio = total current assets / total current liabilities

The ratio provides information about the company’s ability to pay its short-term debt. The more current assets in comparison to current liabilities a company has the better it will be able to pay of the current liabilities. The ratio depends very much on the industry but in general 1.5 is considered a strong ration.

Ratios can be analyzed by comparing them over time or benchmarking them to the industry.

- Debt ratio = total liabilities / total assets

This ratio provides information about the ability of a company to pay of its debt. It indicates which percentage of the assets is paid by liabilities. Unlike the current ratio, a lower debt ratio increases the financial strength.

Chapter 4: Internal control & cash

This chapter deals with fraud its impacts and how a company can design an effective control system to protect from fraudulent behavior.

Fraud and its Impact:

Fraud is often considered the ultimate unethical act in business. Yet the past decade has been full of examples of fraud within large corporations, Enron, WorldCom and Satyam Computer Service (beginning of chapter example) just to mention a few. Surveys indicate that approximately 75% of companies have experiences fraud, also referred to as “cooking the books”. In general fraud is a misrepresentation of facts in some sort. This can take two forms:

- misrepresentation of assets – employees steeling from the company and hiding the traces by misrepresentation of e.g. inventory.

- Fraudulent financial reporting – mainly managers are attempting to convince external parties from the financial strength and success of the company by false entries in the books.

For fraud to occur usually the following three elements are present:

- Motive – feeling underpaid, need of money, being smarter than the system

- Opportunity – missing internal control, weak control environment etc.

- Rationalization – an excuse to rationalize the action to make one self believe that it is not unjust or illegal.

In order to protect from fraud companies need to establish an effective internal control system. This serves the following five purposes:

- Safeguard – protect the assets from inefficiency and fraud

- Encourage employees to follow company policy – promote clear policy and fair treatment

- Promote operational efficiency – minimize waste

- Ensure accurate, reliable accounting records – without reliable records there is no information to base management decision on.

- Comply with legal requirements – Sarbanes-Oxley Act (SOX)

The Sarbanes Oxley Act has been passed by US congress in 2002 as an answer to Enron and WorldCom. It aims at increasing internal and external auditing of large companies. The following are the main four provisions:

- Every public company must publish an internal control report. This report is acknowledged by an external auditor.

- The Public Company Accounting Oversight Board has been established to monitor the auditing process of publicly listed companies.

- Accounting firms cannot audit and consult one client at the same time.

- Security fraud can lead to 25 years in prison, false sworn statements 20 years.

When designing an Internal Control system managers should consider the following five elements (in the book shown as a house):

- Control Environment (roof) – from the top down managers need to make the importance of internal control clear. This can be formalized by an corporate code of ethics.

- Risk Assessment (chimney) – a company needs to indentify the transactions or links that are under the risk of fraud.

- Information System (door) – these are the channels through which information enters and leaves the company. Special attention needs to be drawn towards true representation of these information in the journals and records.

- Control Procedures (keyhole) – how are the five objectives of internal control (discussed before) secured? In more detail below.

- Monitoring of Control (windows) – ensure that no single employee has enough responsibilities to commit fraud without other employees realizing it.

Internal Control Procedures are the backbone of the internal control system. By designing them correctly a company can minimize the risk of fraud. The following five procedures should be considered:

- Smart Hiring Practices and Separation of Duties – When running background check during hire, providing proper training and pay competitively, the risk of fraud is reduced. Further, duties should be split between employees to ensure mutual monitoring. This applies especially to asset handling, record keeping and transaction approval.

- Comparison and Compliance Monitoring – the processing of transaction should be designed in a way to allow easy cross-checking by different employees. Use of operating budgets and cash budgets can support this effort. During this process it is easy to spot exceptional variances between the budgets. Finally regular internal and external auditing processes should ensure reliability of the books.

- Adequate records – companies must keep adequate records of past transaction. These can exist in paper or electronic form.

- Limited Access – companies should limit employee’s access to assets to the amount required for their work. In addition access to records should be protected by safes or passwords.

- Proper Approval – access to assets and transactions should require the proper approval of a manager. This responsibility can also be delegated to another department. E.g. sales on account receivables need to receive approval from a credit check department.

One can remember the five elements by remember in the word SCAPL.

Smart hiring and Segregation of duties

Comparison and Compliance monitoring

Adequate records

Limited access to both assets and records

Proper approval

Modern technology has changed the implementation and risks of internal control systems. Controlling certain kinds of assets became a lot easier. For example checkpoint systems can use as alarm system when goods are leaving the inventory or stores without being scanned. On the other side, especially e-commerce bears additional risks. The tree main risks from e-commerce are stolen information (such as credit card numbers), computer viruses and phishing expeditions. Phishing takes place when bogus homepage are created to mimic an existing homepage.

The main limitations of internal control systems are cost benefits analysis. Although internal control is crucial, its measures still need to stand in a healthy relation to its costs.

The Bank account as control device:

As cash is the most liquid asset, special care is necessary to control its flows. The following five documents are used to control bank accounts.

- Signature cards

- Deposit tickets

- Cheque

- Bank statement

- Bank reconciliation

Bank statements are sent regularly by the bank to the company, in order to inform them about all transaction that took place during the period. These statements need to be compared to the cash account in the company’s ledger (if you forgot what a ledger is, take a look at chapter two again). This comparison is done by preparing the bank reconciliation. The reconciliation sheet shows on the left side all the information from the bank and on the right side all the information from the company’s books. The aim is that after having done all adjustments both sides show the same balance. The following adjustments need to be done:

Bank side:

- Deposits in transit – they need to be added to the bank account as they took place but are not yet shown on the bank account.

- Outstanding cheques – they need to be deducted as the company recorded these expenses but money was not yet withdrawn from the account.

- Bank error – account needs to be corrected for past errors

Book side:

- Bank collection – the bank collected money for you, this needs to be added.

- Electronic fund transfer – firm needs to adjust for automatic ECTs

- Service charges – need to be deducted

- Interest revenues on your cheque account – needs to be added

The bank reconciliation is a simply way to spot errors and fraud concerning the handling of cash.

Cash receipts:

If cash is receipt in stores, this should be organized centralized at so called point-of-sales. All the cash receipts from the points-of-sales in store are the perfect way to track record the amount of cash received. When comparing them to the bank statements controllers can spot missing cash. If cash enters the company by mail, there should be a twofold system. From a centralized mail room the original should move to the treasury, while a copy is send to the accounting department. In the end the controller can compare the information in the books with the bank account and ensure that all cheques found their way to the bank. This is another example of segregation of duties.

Control over cash payments:

Here as well the principle of segregation of duties applies. In general the process of ordering and paying involves three stations.

- Purchase order – a purchase order form is recorded

- Invoicing – together with the goods the supplier sends an invoice (the bill)

- Receiving Report – the receiving report acknowledges the entry of the goods and triggers the payment.

All three documents should be processed by different people or departments. After processing each document should be invalidated to ensure that no invoice is paid twice.

Chapter 5: Short-Term investements & recievables

This chapter deals with financial investments. In general there are three types of financial investments, financial assets (mainly short-term), investments in associations (manly long-term) and investments in subsidiaries (mainly long-term). Financial assets consist of:

- Trading securities

- Loans and receivables

- Held-to-maturity (investments)

- Available-for-sale (investments)

All of these four categories mainly consist of short-term investments. This chapter deals only with trading securities and receivables. This is because held-to-maturities are simply bonds and available-for-sales are all other financial instruments that do not fit into one of the other categories.

Trading Securities are short-term investments in marketable securities. Marketable securities are all investments that are traded on an institutionalized liquid market, such as shares and bonds. Trading securities are purchased by companies with the sole purpose to invest free cash and make a short-term profit, opposed to shares in companies that are hold with the purpose of have some control over the entity. The official name under IAS (international accounting standards) is “Fair Value through Profit and Loss”.

There are four transactions in connection with trading securities.

- Purchase of the security

- Receiving dividends from the investments

- Unrealized gains/losses

- Selling the security

The first transaction is the most straightforward one. It works just as we have learnt in the previous chapters. The cash account (if paid in cash) is credited while the asset account “Investment in XY” is debited. In essence this is a reallocation of assets, thus the total balance of the balance sheet as well as the income statement remain unchanged.

If the security pays dividends the company has to book these as an income. The journal entry is shown here. Assets and shareholder’s equity increase with this transaction.

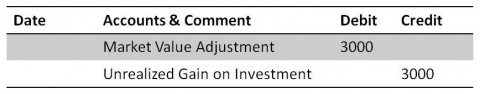

Unrealized gains and losses occur at the end of the accounting period due to the change of value of the security during the period the company holds the investment. These gains and losses are unrealized as the company did not sell the investments and therefore did not yet realize the change in value. This method of valuation is called fair value. It measures the worth of an investment not only at the moment of purchase and sale but on an ongoing basis and accounts for it at the end of each accounting period. If the value of the investment increases by 10 (e.g. the stock price rises) the following journal entry occurs:

| Date | Accounts & Comments | Debit | Credit |

| Dec 31st | Investment XY | 10 | |

| Unrealized gain on investment | 10 |

Unrealized gain on investment is a shareholder’s equity account and thus increases with a credit booking. If the value decreases during the year the following journal entry occurs:

| Date | Accounts & Comments | Debit | Credit |

| Dec 31st | Unrealized loss on investment | 10 | |

| Investment XY | 10 |

Unlike depreciation in a PPE account the gain or loss does not impact an contra asset account but directly the debit/credit side of the investment account. Thus the value at the moment of purchase is not instantly clear from the statements.

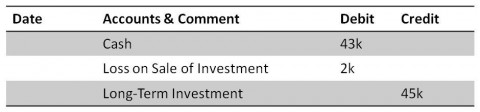

The moment the investment is sold the following transaction occurs:

| Date | Accounts & Comments | Debit | Credit |

| May 31st | Cash | 120 | |

| Gain on investment XY | 10 | ||

| Investment XY | 110 |

Remember the investment had an initial value of 100. We adjusted the value on Dec 31st by 10 due to fair market value. In May we sell it for the 110 plus 10 more, which represents the increase in value from December to May.

As long as the company holds the trading security it is part of the current assets on the balance sheet. All changes in value and dividends occur on the income statement as income or expense.

Account and Notes Receivables

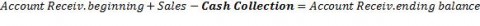

This category of short-term investments is usually the third most liquid asset (after cash and trading securities). They represent monetary claims again another entity. Account receivables usually arise from selling goods or services to customers on account, meaning that they pay later. Notes receivables are more formal contracts which are often used for short-term lending but can also be used as part of a sales transaction. These contracts usually state the maturity, maturity date (date when the debtor has to pay) and the interest. Usually every debtor, customer or supplier, has its own account. The accounts receivable account on the balance sheet shows the overall consolidated balance of all individual accounts. In relation to the discussions in chapter four, it is very important to separate the cash-handling duties and the accounting duties, to prevent fraud.

Selling on account has risks and benefits. On the one hand it can potentially increase sales, by allowing customers to buy goods although they are only able to pay in the future. On the other hand there is a risk of not collecting the full amount of account receivables. These costs are booked as uncollectible-account expenses, doubtful-account expenses or bad-debt expenses.

Accounting for uncollectible receivables can be based on two methods, allowance method and direct write-off method. However the later one is not generally accepted. The IAS requires certain conditions before a company can declare receivables as uncollectible. There must be objective evidence of one of the following events:

- Significant financial difficulties

- Breach of contract

- Adverse change in a number of delayed payments

- National or local economic conditions

These events MUST occur after the contract or sales transaction was done. Conditions prior to the contract are believed to be taken into consideration when agreeing on a transaction. The allowance method works in two steps. First, one has to estimate which percentage of the receivables is uncollectible. Secondly, the amount uncollectible is booked on a contra account to account receivables. This follows the same logic as the accumulated depreciation in chapter 3.

Estimating the amount uncollectible:

The best approximations of the amount of receivables a company cannot collect are usually historic track-records. This is often done by a method called aging-of-receivables. In a first step each customer’s receivables are allocated according to how long they have been outstanding. In a next step, one has to estimate the percentage uncollectible for each time horizon. This should be based on past data. Finally one multiplies the total outstanding receivables in each period with the percentage assigned and sums the results. This gives the total expected value of uncollectable receivables. The whole process can be shown in a table like the following:

| Recievables | Not Due | Due since 1-30 days | Due since 31-60 day | Due since 61- 90 days | Total |

| Costumer X | 200 | 100 | 50 | 0 | 350 |

| Costumer Y | 500 | 100 | 300 | 100 | 1000 |

| Costumer Z | 600 | 100 | 700 | ||

| Total | 1300 | 300 | 350 | 100 | 2500 |

| % assigned | 1% | 5% | 10% | 20% | |

| Required allowance | 13 | 15 | 35 | 30 | 83 |

In this case, the total receivables are divided by customer and into four time horizons, depending on their time outstanding. From the table we can infer that of the total amount of receivables we expect to 83 to be not collectable. However, one shortcoming becomes apparent when comparing customer Y to the other customers. While X and Z seem to have declining amounts outstanding the older their debt, customer Y seems to have a history of not being able to pay. In order to improve the prediction delivered from this method companies should also analyze the credit history of each customer individually.

The next step is to book the uncollectible amount. As previously stated, this is done in a similar fashion as accumulated depreciation. The following shows the required journal entry.

| Date | Accounts & Comments | Debit | Credit |

| Dec 31st | Uncollectible Account Expenses | 83 | |

| Allowance for doubtful reciev. | 83 |

As this transaction decreases the expected income the debit account is an expense account, namely Uncollectible-account expenses. However, the credited account is NOT the account receivables but its contra account “Allowance for doubtful receivables” or “Allowance for uncollectable receivables”. In this way the original amount of receivables is preserved. At the bottom line this transaction decreases assets as well as shareholder equity. In case there is already a previous booking in the account for uncollectible receivables, make sure to only book the additional balance required.

In the previous example we just calculated the expected amount uncollectible, based on historical data. However, as soon as we know for certain that a customer defaults on his debt; we need to cross the debt from our books (writing it off). This is done with the following transaction:

| Date | Accounts & Comments | Debit | Credit |

| Dec 31st | Allowance for doubtful reciev. | 20 | |

| Account recievables costumer Y | 20 |

The contra account, we previously built up, is reduced by the amount of default. On the other hand the customer’s receivable account is also reduced by 20. As we have already accounted for an expense the moment we booked on the contra account (allowance for doubtful receiv.) this event does not represent an expense anymore.

| Debit | Credit |

| 20 | 83 |

After the transaction the t-account for the uncollectible receivables will look as shown above. To calculate the ending allowance at an accounting period one can remember the following relation:

Beginning allowance - receivables write off + new bad debt = ending allowance

If a company uses the direct write-off method it basically skips the first two steps (estimate the amount and booking on the contra account) and directly writes the debt of the customer account. As this write-off can only occur when there is certainty about the situation of the debt, this method does not account for risk of future defaults. As previously said it is therefore not generally accepted.

The ending balance of the account receivables can be calculated using the following relation:

Beginning receivables + sales – write-offs – cash collections = ending receivables

Notes Receivables:

Several key terms are important to remember when dealing with notes receivables:

- Creditor – the party that lends the money or good

- Debtor – the party that borrowed the money or good

- Interest – the cost of borrowing, always stated in a percentage per year

- Maturity date – date on which the note is due (money has to be paid)

There are three transactions associated with notes receivables.

1. Lending money:

In this case cash is reduced and therefore the asset note receivable is built up.

2. Receiving interest- although the interest is usually only paid on the maturity date together with the principle sum, the company has to account for the revenue at the end of the accounting period.

In case the interest is 10% and on December 31st it has been outstanding for 6 month, the company has to account for 5 of revenue (100*0.1*6/12).

3. Maturity date:

On this date the full amount is paid in cash. The principle (100) is booked against note receivable. The interest from the previous period is booked out again and the remaining interest is right away booked as revenue for this period. Always remember that the interest is expressed as per year!!

Speeding up the cash flow can be very important for companies, as it decreases the time period during which they have an investment deficit (between paying their suppliers and receiving from customers). There are two ways how cash flows from sales can be speeded up.

- By offering credit card or bankcard payments the company received the payment right away while it allows customers to pay the bill later (usually one month). However this comes at a certain cost to the company, usually about 4%.

- Factoring / selling receivables describes the process of selling the debt to another company and receive cash right away. A factor business usually applies a relatively high discount rate to the value of the debt.

Finally there are two important accounting ratios concerning receivables:

- Acid ratio= (cash+short-termin investment + net current receivables) / (total current liabilities)

This ratio describes a company’s ability to pay of their current liabilities. Usually firms aim at a ration at more than 1.

- Days’ sales in receivables = (average receivables * 365) / (yearly sales)

This ratio provides an indication of how many days the company needs on average to collect its receivables.

Chapter 6: Inventory & Costs of Goods sold

This chapter deals with how to account for inventory and cost of goods sold. This understanding will help you to further understand financial statements.

Account for inventory

Accounting for merchandise inventory is done in several ways:

- On the balance sheet: you report a product when a company still holds in inventory. Therefore, this is an asset.

- On the income statement: reports the costs of the products sold (costs of goods sold). Here, it is an expense.

Therefore, inventory changes from an asset to an expense as soon as the product is sold, and thus transferred to the buyer. Moreover, there is a distinction between the sale price and the cost price of inventory. This distinction serves several purposes:

- The sales revenue is based on sale price

- The cost of goods sold is based on the cost

- On the balance sheet, remaining inventory is recorded on its cost

To report inventory on the balance sheet, you use the following formula:

Inventory (balance sheet) = # of units on hand x cost per unit of inventory

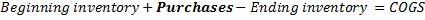

Cost of goods sold is calculated with the following formula:

Cost of goods sold (Income statement) = # of units of the inventory sold x cost per unit of inventory

If you deduct the cost of goods sold from the revenue, you get the gross profit (or gross margin), as you have not subtracted operating expenses yet.

The number of units of inventory is determined in the accounting records. Units held on consignment are not included; these are products that a company holds for another company. However, products another company holds on consignment for you are included in the count of units of inventory. Free on board (FOB) indicates who owns the products at the time and must therefore pay for the shipping. FOB shipping point indicates that the legal title to the goods is transferred to the purchaser once the goods leave the seller’s place. FOB destination means that the title is only passed upon arrival at the purchaser’s place. Cost per unit of inventory can be calculated in different manners, which will be discussed next.

Before coming to the actual costing methods, it is important to understand the difference between the two main types of inventory accounting systems:

- Periodic inventory system: used for inexpensive goods. Companies count their inventory periodically (at least once a year).

- Perpetual inventory system: constantly records the inventory on hand and used for all kinds of goods. Most businesses use this type of inventory system. A company that uses this system should still count the inventory on hand annually, because of the financial statements and a check upon the perpetual records.

All accounting systems record every purchase of inventory; two entries are needed in the perpetual system in case of a sale:

· Record the sale: debit the cash/accounts receivable and credit the sales revenue.

· Cost of inventory sold: debits cost of goods sold and credits inventory.

The cost of inventory is calculated next:

Net purchases = Purchases

- Purchase returns and allowances

- Purchase discounts

+ Freight-in

Freight-in is the transportation cost, which is paid by the buyer, and is accounted for as part of the costs of inventory. This only applies when it is agreed upon under the FOB shipping point terms. Purchase returns decrease the cost of inventory, in order to approve these returns a company draws up a debit memorandum, which reduces the account payable (debits) for the amount goods are returned.

Net sales are computed in the exact same manner:

Net sales = Sales revenue

- Sales returns and allowances

- Sales discounts

Inventory costing methods

Costs of inventory include all the costs associated with inventory to make it ready for sale. However, advertising costs and sales commissions are not part of these costs.

If costs were to remain constant forever, costs would be easily determined per unit; this is unfortunately not the case. Therefore, specific identification is needed when assigning costs to products held in inventory. This is an expensive method, and not very applicable if items share some characteristics.

There are three common cost formulas: first-in, first-out (FIFO), last-in, first-out (LIFO) and average cost method. These methods assume different flows of inventory costs, and thus not the specific identification of costs.

FIFO cost

In this method the products that first came in, also have to go first out. This means that when you have products that have different costs, the first that came in will go out first. Therefore, for calculating the cost of goods sold and the inventory at hand, you should take this into account.

LIFO cost

Here it is different from FIFO, as the products that last came in will first go out. Therefore, the products purchased last, will leave inventory also the earliest. To account for both COGS and Inventory on hand, it is important to understand this distinction.

Average cost (or Weighted Average Method)

This method “averages” the costs for all purchases. Therefore, COGS and Inventory on hand will be based on the same cost. The average cost per unit is calculated as follows:

Cost of goods available*

Average cost per unit = ------------------------

Number of goods available*

*goods available = beginning inventory + purchases

When inventory unit cost change, the three distinct methods have different effects on the financial figures:

- Cost of Goods Sold (COGS). LIFO depicts the most realistic figure, as it uses the most recent numbers. FIFO uses the oldest inventory costs, which is not an appropriate measure for the expense.

- Ending Inventory. FIFO uses in this case the most realistic information. LIFO can value inventory at very old cost, which might not be very up-to-date.

The weighted average is most of the times right in between these two methods.

Accounting principles

Comparability principle entails that a company should use the same accounting methods from period to period, as this consistency enables investors to compare financial statements from one year to another. Companies can still change their methods, but it should be clear that this has been done, so people can take it into account when comparing data.

IAS2 also requires companies to record the costs of inventory of the lower of cost and net realizable value (NRV). So, you have to compare the cost (established by FIFO, LIFO or WA) and the NRV, and the one that’s lower should be used. NRV is the estimated selling price (for normal business) minus the estimated costs of completion and the costs necessary to make the sale. If inventory is written-down to the NRV value, it is recorded as an expense in the period of write-down. After this it is just seen as a decrease in COGS.

Ratios are used to evaluate how well a business is doing. You have two ratios that are directly linked to inventory:

- Gross profit percentage this is also called gross margin percentage. It is the mark-up stated as a percentage of sales. The percentage normally changes little from year to year, so if there is a small downturn trouble may be ahead. You can calculate it with the following formula:

- Inventory turnover this is the ratio of COGS to average inventory, which indicates how fast inventory is sold. It indicates how many times a company sold its average inventory during the year, and calculated as follows:

Inventory turnover = cost of goods sold / average inventory*

*Average inventory = (beginning inventory + ending inventory) / 2

This can also be expressed in days, which is called the inventory resident period, which is calculated by dividing 365 by the turnover. This number varies per industry.

Cost-of-goods-sold model can be used to manage business effectively. It looks at what merchandise to offer to its customers (a marketing issue). And it looks at how much inventory it should buy or produce, which is an accounting issue. The model is depicted below.

Beginning Inventory | 1,000 |

+ Purchases | 5,000 |

= Goods available | 6,000 |

- Ending Inventory | 1,200 |

= Cost of goods sold | 4,800 |

Estimate inventory with the gross profit method

With the estimated gross profit rate you can estimate the costs of ending inventory, in case you need to know due to e.g. fire. The method is almost the same as the COGS model; it only rearranges ending inventory and COGS the other way around. Goods available minus the COGS will indicate the ending inventory. If the gross profit rate is known you can deduct the estimated gross profit from the net sales, which will then account for the estimated COGS.

Effects of inventory errors

If inventory is overstated, it will balance out in the next period, as beginning inventory is then also overstated. However, the information is in this case not accurate for the individual periods.

Fraud concerning inventory is mostly committed in one of two ways:

- Fictitious inventory is accounted for, thus overstating the actual quantities;

- Using higher unit prices for the ending inventory

Chapter 7: Plant Assets & Intangibles

During the last two chapters we learned about the different types and transactions of current assets, such as short-term investments, receivables and inventory. This chapter deals with non-current assets. There are four main classes of non-current assets:

- Property, Plant and Equipment (PPE) – these are also called fixed assets

- Construction on Progress – as the building of a non-current asset (such as a new plant) can take years there is an extra class for the value of the construction on progress. Typically upon completion the value is transferred to PPE

- Intangible Assets – any identifiably asset that has no physical form

- Investment Properties – this rather rare form of non-current assets contains investments that are not hold for trade but for income trough rental or capital appreciation

Every PPE asset is subject to deprecation, besides land that is owned in perpetuity. In the case of natural resources, such as mines, the expense is not called depreciation but depletion. Intangibles do not depreciate but depending on their nature they might be subject to amortization, we will revisit that later. In essence depreciation is a method to spread the total costs of the asset over its lifetime, in order to match revenues from that asset to its expenses.

Without any special events, depreciation follows the following three steps.

- Determine total cost of asset

- Decide upon a depreciation method

- Calculate and book the depreciation

When determining the total cost of an asset one has to recognize all the costs that are necessary to bring the asset to its intended use. In general for PPE this can include all the following:

- Purchase price – including all taxes and duties

- Transportation cost

- Labor cost – related to constructing or buying the asset

- Installation, testing and site costs

Not included should be for example overhead costs.

In the case of purchasing land, the total cost will include expenses for gardening or cleaning the land. However, expenses for paving, fencing or securing the property are not part of the initial costs.

Sometimes assets are purchased in bundles, for example in the case of a factory on a piece of land. In this case the relative-sales-value method is used to assign the initial costs to each asset. If the total amount was 1 million and the land is worth 200k on a free market, while the factory is worth 900k, the million will be split into 2/11 and 9/11.

Once an asset is purchased, up and running all addition cost will either be expensed or capitalized. “Expensed” means just that the cost are accounted for as an expense, while “capitalized” costs are added to the value of the asset. Only expenditures that increase the assets lifespan or capacity should be capitalized. This could be modifications, expansions or major engine overhauls. It is crucial to be very aware about the decision of expensing or capitalizing as it has a direct influence on the company’s income. Take a look at the two examples:

- If costs are expensed instead of capitalized, then expenses are overstated and therefore income understated.

- If costs are capitalized instead of expensed, then expenses are understated and therefore the asset as well as income overstated.

In the past there have been many accounting frauds concerning the decision of capitalizing or expensing. The most well known one is WorldCom who capitalized expenses to overstate income during the economic downturn in 2001.

There are three depreciation methods:

- Straight-line depreciation

- Units-of-production

- Double declining balance (an accelerating depreciation method)

For all three methods we need to know the following things about the asset:

- The costs of the asset

- The estimated useful life – physical wear and tear, obsolescence or expiry date

- Estimated residual value – how much is the asset worth after its lifetime is over; this is often referred to as scrap or salvage value

The straight-line method is by far the most commonly used method. It spreads the total cost of the asset evenly over its lifespan. The yearly deprecation is calculated with the following relation:

Cost - Residual value

Straight line dep per year = ---------------------

Useful lifetime

The journal entry for depreciation is the following:

| Data | Account & Coatments | Debit | Credit |

| 10th of May | Depreciation Expense | 100 | |

| Acculumlated depreciation | 100 |

Remember that depreciation is booked on accumulated depreciation, which is the contra asset account to the according asset account. This transaction decreases shareholder’s equity by the yearly depreciation.

The following example shall help you remember straight line depreciation. Imagine you always want to drive the newest Mercedes. If you know that every 5 years there is a new model coming out, your assets life span is 5 years. The Mercedes costs 50.833 + 20% tax = 61.000. Further you know that you can sell the Mercedes after 5 years for 11.000. Therefore you can calculate that the yearly deprecation is (61.000 – 11.000) / 5 = 10.000. So per year you have an expense of 10.000 to drive your Mercedes (plus repair and gas or course). If you did personal account, every year the accumulated depreciation account increased by 10.000, while your carrying asset amount in the balance sheet(cost-accumulated depreciation) decreases.

Unit-of-production method:

Instead of spreading the costs evenly over the lifetime, this method spreads the costs evenly over the total expected output during the lifetime. This method is only useful for factories or other PPE where total production can be estimated.

Cost - Residual value

Depreciation per unit of output = ------------------------------

Useful life in number of production

The journal entry is the same for each deprecation method.

Double-declining-balance (DDB) method assigns higher expenses in the beginning of the use of the asset than in the end. You first calculate the straight-line-deprecation, ignoring the residual value, and then double it, in order to receive the double decline balance depreciation. For example if the lifetime is 5 years the DDB rate is 40%.

There are two important things to remember:

- The depreciation expense is always calculated by multiplying the DDB rate times last year’s asset carrying amount. By doing so the depreciation expense decreases over time.

- The depreciation in the last year is calculated by deducting the residual value from the asset carrying amount of the previous year.

IAS requires companies to choose the depreciation method that best reflects the pattern of consumption. It is allowed to use different depreciation methods for different assets.

Depreciation for tax purposes:

As the choice of depreciation method has a direct impact on the company’s income, it also has an impact on the amount of taxes a company has to pay. Thus, certain jurisdictions often require a certain deprecation method for certain asset classes. If this is not the case companies will often try to apply the accelerated depreciation method in their statement for the tax authorities. This method assigns the highest cost to the early years, which leads to a reduction of tax burden during these years. The free cash can be used for other investments or to pay off debt.

Change in Estimates of useful life:

Due to certain circumstances it can happen that a company has to adopt their estimation of the lifetime of an asset. For example if a product line will be obsolete earlier than expected, the factory is also likely to be out of use earlier. This recalculation is done in the following way.

Newly yearly depreciated = (asset carrying amount (asset - accumulated depreciation)) /new lifespan

In case of a shorter lifespan the deprecation will be higher and therefore the shareholders equity lower.

Impairment of PPE:

If a company realizes that due to changing circumstances the asset carrying amount is significantly higher then re recoverable value the asset has to be impaired. This is basically an adjustment of the value of the asset, for cases such as suddenly outdated technology or changing jurisdiction. The amount of impairment loss is the difference between the carrying amount and the recoverable amount.

Disposal, selling and exchange of PPE:

After the assigned lifetime of an asset is over it can be used on. In this case no further depreciation will be assigned and the asset as well as the depreciation account will stay in the balance sheet. However if a company disposes an asset the accounts have to be written off.

If the asset has not been fully depreciated the outstanding deprecation would be booked as an expense.

If an asset is sold it is important to calculate whether it was sold for an profit or a loss:

Cash received – (cost of asset – accumulated depreciation)

The gain is calculated by value of new car - (asset carrying amount+ cash).

Natural Resources:

When dealing with natural resources one has to account for depletion instead of depreciation. The method of calculating depletion is exactly the same as the per unit method for depreciation.

Intangible Asset:

There are five main categories of intangibles assets:

- Patents

- Copyright

- Trademarks

- Franchise and License

- Goodwill

One has to differentiate between finite and infinite intangible assets. Finite intangible assets are subject to amortization (works the same as straight line depreciation). This has to be decided on a case by case basis, however Goodwill is always an infinite asset and therefore not amortized.

Goodwill describes the additional value a company has over the sum of the fair values of its assets. For example when purchasing Apple one has to pay more than simply the value of all its stores, factories and patents. IAS allows companies only to report goodwill if it was created by M&A.

The purchased company had assets worth 100 million and liabilities worth 30 million. Therefore the market value should be 70 million, but it 80 million were paid for. These remaining 10 million are accounted for as goodwill.

Intangible assets (even Goodwill) can be subject to impairment. This works exactly the same ways as for PPE.

When accounting for R&D costs, IAS differentiates between research and development. Research costs are always expensed while development costs can be capitalized if they fulfill the following conditions:

- Feasible

- Intention to complete

- Ability to use or sell

- Expected future economic benefit

- Reliable measure for expenditures exists

Chapter 8: Liabilities

This chapter deals with the different kinds of liabilities, their journal entries and pros/cons as financing method. First I will discuss current liabilities, followed by long-term liabilities and finally non-current liabilities.

Current Liabilities

This category contains liabilities that are due within one year. One can differentiate between current liabilities with known amounts and those with unknown amount. First we will take a look at the different forms of current liabilities with known amounts. In general you have to consider the following seven categories:

- Account Payable – as discussed in chapter 4 this account consist of amounts owed due to unpaid products or services.

- Short-term notes payable – a form of short term financing. The interest or accrued interest is booked as discussed in chapter 3.

- Sales Tax Payable – Companies collect in addition to their sales revenue, the sales tax or value added tax. As this collected amount is actually owed to the government, it is recorded as a liability until transferred to the government. While sales revenue increase shareholder’s equity, sales tax payable increases liabilities.

Date Accounts & Comments Debit Credit Cash 100k Sales Revenue 90k Sales tax payable 10k - Accrued Liabilities – accrued liabilities arise from expenses that have been incurred but not yet paid. This has already been discussed in detail in chapter 3.

- Payroll Liabilities – this includes all the partial or total compensation for employees that is still outstanding. Income tax payables are also part of payroll liabilities. They are booked just like sales tax.

- Unearned Revenues – these are revenues that have been collected in advance of performance, thus they are a liability to deliver a good or service at a later stage. This category has also been dealt with in chapter 3 (deferred revenues).

- Current Portion of non-current debt – if portions of long term debt have to be paid within a year it is reclassified as current debt.

Current Liabilities with unknown amount

There are many examples for liabilities of which the company knows they will occur but not the exact amount. This can be the case for lawsuits, tax claims or warranties. In these cases the amount has to be estimated as good as possible to build up a provision. For example if a company sold 1 million worth of radios with a one year provision, it has to assume the amount of radios that will break. If 5% have to be replaced a provision is built at the moment of purchase of 1 million x 5% = 50.000. The provision account is a liability.

| Date | Accounts & Comments | Debit | Credit |

| Warrenty expenses | 50000 | ||

| Provision for warrenty repairs | 50000 |

Contingent Liabilities are not recorded in the balance sheet. They occur if either the event that would trigger the obligation is completely out of the control of the entity or a proper estimation of the amount of the liability is not possible at all.

Cooking the books – deliberately understating liabilities is not allowed as it would overstate the financial situation of the company.

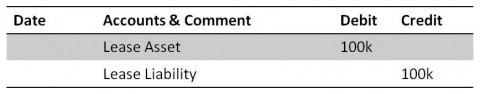

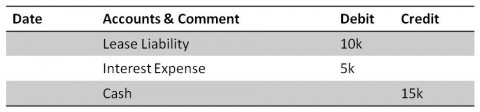

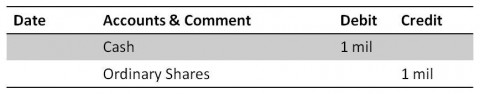

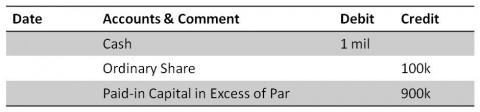

Long-term Liabilities – Bonds