There is no overarching body that imposes laws, policy tools, currency, taxes and barriers on nations. Nations have their own policy and being sovereign makes them less likely to compromise and more likely to ignore foreign interests. On the other hand, regions have to obey nationwide rules and have less policy tools at their disposal than nations. This makes them more likely to compromise and distincts national economics from international eonomics. Four controversies will illustrate the special nature of international economics.

Which four controversies illustrate the special nature of international economics?

U.S. exports of natural gas

The example of the United States (U.S.) exporting natural gas clearly shows the influence of international trade. The U.S. has had a flat production of natural gas for several years while it faced increased consumption. At the same time, the production costs increased due to the exhaustion of available sources. U.S. imports increased to meet the increased demand. Just when it seemed they had to increase these high-cost imports of natural gas big time, technological developments enabled the U.S. to extract natural gas from newly accessible sources. U.S. firms increased production of natural gas for several years and could even look for new customers outside their own country. However, a U.S. law prohibited exporting unless it would be in the public interest. This raised the question how and whether the public interest would benefit from exporting natural gas. Some people were afraid that the U.S. would export all of its gas away or that it would be too costly. However, following the 2011 tsunami and its destructive aftermath, Japan shut down its nuclear facilities and increased its demand for natural gas to generate electricity. If the U.S. and Japan would open up to trade, the following would happen:

- An equilibrium would result in the international natural gas market if the U.S. would export to Japan. Increased demand for natural gas would drive up its price, increasing U.S. production and decreasing U.S. consumption in turn. The price in Japan would actually fall, increasing consumption there.

- Not everyone will benefit from trade. Due to an increased U.S. price, consumers will be harmed but producers and exporters will benefit.

- Environmental effects aside, most people are better off. Despite a higher international price, the U.S. won't export all of its gas since transportation costs are significant.

Immigration

Immigration has some economic effects as well. Again, there is a net economic benefit. Job-seeking immigration benefits employers of immigrants and consumers who buy the products produced by them. However, since residents who compete with immigrants for jobs are usually worse off, there will always be fights over immigration.

China's exchange rate

The exchange rate is a key price in international economics. It is a powerful tool to influence flows of goods and services as well as financial flows. The Chinese government illustrated this by fixing the exchange rate between the yuan and the U.S. dollar. According to the U.S. and the European Union (EU), the yuan was valued too low. This increased demand for the yuan. Normally, the price of the yuan would increase but China chose to intervene to keep a competitive advantage and run a trade surplus. The Chinese government kept buying dollars with yuan and was pressured by the U.S. and the EU to end this 'unacceptable' currency manipulation. China kept resisting this pressure but started to experience the downside of the fixed exchange rate as well. The lower value of the yuan and its increased supply encouraged local borrowing and spending, putting upward pressure on its inflation rate. Therefore, in the end China could benefit from allowing the exchange rate of the yuan to increase.

This example illustrates that (international) trade usually results in an equilibrium. Deviations from this equilibrium tend to be temporary and result in shifts toward an equilibrium.

Euro crisis

The global financial and economic crisis and the Euro crisis clearly show the interrelatedness of nations' economies and the controversies that result from trade agreements. Loans in the U.S., especially mortgages, of low-risk borrowers were packaged with those of high-risk borrowers and sold with a good credit rating. This encouraged a credit boom that funded a housing bubble. The subprime mortgages of high-risk borrowers increasingly went into default and with them the packaged securities. All of a sudden, credit ratings were unreliable and the financial markets froze as financial institutions and investors became reluctant to lend to each other. Europe was involded in four ways:

- Housing bubbles and credit booms were also present in Ireland, Spain and other European countries;

- European banks also held subprime mortgages and (as it turned out) worthless packaged securities;

- European banks in need of short-term funding were harmed since financial markets froze;

- The U.S. financial crisis became a recession which spread to other countries when U.S. production and income, and hence, imports, declined.

The development of a monetary union was crucial in integrating financial markets across the euro area and has been really successful. Following the recession, however, the EU was under pressure to help several countries meet their financial obligations. Without intervention, severe losses would be made and the continuence of the union and its currency would be under pressure. Bailouts occured but institutions and investors were still reluctant to invest in certain government bonds, driving up their interest rates. The European Central Bank (ECB) had to intervene with a lot of money and show that it would do whatever it took to preserve the euro in order to restore trust and start recovery from the crisis.

How is international economics dependent on the nation-state?

The previous four examples illustrated the interplay of international economics and nations' sovereignity. Each country has policy tools to influence the international market. Among the most important are:

- Factor mobility: although workers and capital are more mobile within countries, they do move internationally.

- Different fiscal policies: each country can impose regulatory policies on flows of goods, services, financial assets and people like import taxes or export subsidies.

- Different moneys: each country can have its own currency and has policy tools to exert influence on the exchange rate. This means that the value of one currency can change relative to another on a daily basis.

Although there are international organizations like the World Trade Organization, the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank that try to exert some power over the global economy, in the end, countries are sovereign and control their own policies. This is what makes international economics a complex but interesting field of study.

What are the basics of demand and supply?

Every time a product is produced and bought, resources are used which cannot be used for other products. Therefore, producers and consumers have to allocate their resources and make trade-offs. So even when we seem to analyse a single product, we study this product relative to other goods and services in the economy.

Demand

Demand depends on a consumers' preferences, the price of the product, the prices of other products, and income. Demand curves usually slope downward, which indicates that an increase in price lowers demand. This is a movement along the demand curve. The impact of a certain demand characteristic can differ for different types of products. For example, a product is considered a normal good (e.g. clothing) if an increase in income increases demand. A product is considered an inferior good (e.g. pizza) if demand decreases when income increases. It is assumed that in the case of inferior goods, people prefere more expensive alternatives when they have more money to spend.

As a product's price is a determinant of its demand, the quantity demanded is responsive to a change in price. The level of responsiveness depends on the price elasticity of demand. This elasticity measure represents the percent change in quantity demanded when the price increases by 1 percent. Demand is said to be elastic if the absolute value of the elasticity measure is greater than 1. If the absolute value is less than 1, demand is said to be inelastic. This is represented by a steep slope of the demand curve as the quantity demanded does not respond that much to a price change.

When drawing the demand curve, the price of the product itself is included in the model. Therefore, a price change results in a movement along the demand curve. If any other demand characteristic changes - income, other prices, preferences - the entire demand curve shifts.

Consumer surplus

Demand for a product also depends on consumers' willingness to pay. At a given price, it is likely that there is a group of consumers which is willing to pay more. The area between the demand curve and the price of the product in the marketplace represents this higher willingness to pay and is called consumer surplus. This is the net gain that increases the economic well-being of consumers who are willing to pay a higher price but still pay the market price.

Supply

Important supply characteristics are the selling price and the cost of producing and selling the product. Supply curves usually slope upward. Suppliers usually offer extra products as long as the costs of producing and selling the extra units are covered by the selling price. For some products, marginal costs - the costs of producing an extra unit - rise. This means that a higher selling price is needed to cover these extra costs. An increase in a product's price increases the quantity supplied and indicates a movement along the supply curve. A change in any other supply characteristic - availability of inputs, technology - results in a shift of the entire supply curve.

The responsiveness of the quantity supplied to a change in the market price is measured by the price elasticity of supply. This elasticity measure represents the percent change in quantity supplied when the market price increases by 1 percent. Again, a price elasticity greater than 1 is said to be elastic and an elasticity less than 1 is said to be inelastic.

Producer surplus

Given the market price, it is likely that some producers are willing to offer their products at a lower price. The amount between the supply curve and the market price represents the net gain or the increase in the economic well-being of producers who receive the market price but would have settled for a lower price. This is called the producer surplus. Money spend on resources used in production of a given product cannot be spend in other production processes. The value of products not produced because resources are already in use, represents an opportunity cost for the economy as a whole. For an integration of supply, demand, and producer and consumer surplus, see figure 1.

A national market with no trade

If there is no international trade, there is one national price at which the domestic market clears. This is the equilibrium price at which demand equals supply. The amounts of consumer and producer surplus depend on the steepness of the demand and supply curves.

Why do countries trade?

If there is no trade, countries have their own domestic markets with equilibrium prices that are likely to differ. If they open up to trade, arbitrage opportunities arise. This would mean buying something at a lower price in one country and selling it for a higher price in another country to earn a profit.

How does trade affect production and consumption in each country?

Free-trade equilibrium

Arbitrage opportunities will be exploited until the prices in the two countries are comparable. If there are no transportation costs, a free-trade equilibrium price - called the international price or world price - will result. This price can be determined using demand for imports and supply of exports. When two countries have their own domestic equilibrium, the country with the highest equilibrium price will have demand for imports at a lower world price. Excess demand will arise since demand increases and supply decreases when the price drops. The country with the lowest equilibrium price will have supply of exports since the higher world price results in excess supply (decreased demand and increased supply). Eventually, demand for imports is expected to equal supply of exports at the world price. If not, excess supply on the world market would put downward pressure on the price of a trade product and excess demand would put upward pressure on the price.

Effects in the importing country

The importing country would have demand for imports as the foreign price is lower than the domestic price. Moving toward the free-trade equilibrium, consumers are better off at the world price and producers are worse off.

It is hard to say something about the net effect of trade because economic stakes are often dependent on subjective weights. Consumer surplus might increase more than producer surplus decreases but if it results in producers going out of business, is opening up to trade in the nation's best interest? Calculating net national gains means ruling out subjective weights and measuring the effect on aggregate well-being. A useful tool is the one-dollar, one-vote metric which values each dollar of gain or loss equally. If we ignore who experiences it, the net national gains from trade are equal to the difference between aggregate gains and losses.

Effects in the exporting country

The exporting country has supply of exports as the trade price is higher. Moving toward the free-trade equilibrium, producers are better off and consumers are worse off. The net effect can be calculated by comparing the gain in producer surplus with the loss in consumer surplus. To see the effects on the importing country, the exporting country and the world market, see figure 2.

Which country gains more from trade?

When countries open up to trade, the intersection of the demand curve for imports and the supply curve for exports shows the world price. Given this price, the net effects of trade are represented by the area up to the demand curve (for the importing country) and down to the supply curve (for the exporting country). The country with the steeper trade curve experiences a larger price change and thus gains more from trade.

Who are the gainers and losers from opening trade?

Consumers benefit from imported products but are hurt by exportable products. Producers benefit from exporting products but are hurt by imported products.

Every time a product is produced and bought, resources are used which cannot be used for other products. Therefore, producers and consumers have to allocate their resources and make trade-offs. So even when we seem to analyse a single product, we study this product relative to other goods and services in the economy.

The previous chapter focused on trading one product but we would like international trade theory to consider the entire economy. However, since this is very complex, we start to examine a two-product economy in which the countries are a net exporter of one product and a net importer of another product.

What does Adam Smith's theory of absolute advantage teach us?

Simply put, Adam Smith's theory states that a country should focus on producing what is does best. If for example labor productivity - the number of units a worker produces in one hour - is higher, the country is said to have an absolute advantage in producing this product. If two countries devote their resources to the product in which they have an absolute advantage, total world production increases. Countries could trade (part of) their excess production and be better of than when each country produces every product themselves.

What does Ricardo's theory of comparative advantage teach us?

The principle of comparative advantage shows that countries can still gain from trade if one country has an absolute advantage in producing all products that another country has an absolute disadvantage in. Ricardo's theory states that countries should produce the product in which they have a relative advantage.

Suppose that country A requires 4 hours of labor to produce 2 units of wheat or 1 unit of cloth. The relative price of wheat is 0.5 units of cloth and the relative price of cloth is 2 units of wheat. Country B can produce 2/3 units of wheat or 1 unit of cloth which requires 1 hour of labor, so the relative price of wheat in country B is 1.5 cloth and the relative price of cloth is 0.67 units of wheat. Since country A requires so many labor hours to produce the products, it has an absolute disadvantage in producing both products. However, it has a relative advantage in producing wheat. This can be explained using opportunity costs. Country A has to give up half a unit of cloth to produce 1 unit of wheat whereas country B has to give up one and a half units of cloth to product 1 unit of wheat.

Opening up to trade will push the two separate national relative prices of the product toward a new equilibrium price. This world price will fall within the range of the two separate prices. Why? At a lower relative price both countries would want to import it and at a higher relative price both countries would want to export it. In this scenario no trade would result while both countries could be better of by trading.

As shown, countries could benefit from comparative advantage. It should be noted, however, that countries with an absolute disadvantage in all products are still less productive. These countries tend to be poor with low real wages.

What can we learn from the production-possibility curve?

A country can use all its available resources to produce one of the two products or a combination of both. If all resources are used at maximum productivity, we can draw a line representing all possible combinations. This is called the production-possibility curve (ppc). The slope of the ppc represents the relative price of one product in terms of the other or opportunity cost. The ppc is drawn as a straight line when we assume constant productivity because of constant marginal costs.

Assuming that arbitrage opportunities will be exploited when opening up to trade, a line can be drawn representing the world relative price for which the countries can trade their products. As illustrated before, this world relative price will fall within the range of the nation's domestic prices; hence trading along this trade line requires countries to specialize in producing the product in which it has a comparative advantage. This trade line also shows that opening up to trade enables countries to consume more of both products. Therefore, economic theory does not require one country to lose in order for another country to gain. To see how trade enables increased consumption, see figure 3.

The previous chapter focused on trading one product but we would like international trade theory to consider the entire economy. However, since this is very complex, we start to examine a two-product economy in which the countries are a net exporter of one product and a net importer of another product.

In the previous chapter, constant marginal opportunity costs were assumed. Since resources are scarce, it is more realistic to incorporate increasing marginal costs of production. This will be the main focus of this chapter.

How do production possibilities change with increasing marginal costs?

The production-possibility curve is bowed out when we assume increasing marginal costs. As mentioned before, the slope of the ppc represents the relative price or opportunity cost of the two products. If we move along a bowed out curve toward full specialization, opportunity costs increase. Why? Usually, production requires different resources or factor inputs like land, labor and technology. Producing wheat requires relatively more land while producing cloth is labor-intensive. If a country would like to specialize in producing wheat and reduces cloth production, labor resources will become available. Adjusting wheat production so that these workers can be used in producing wheat will be costly; hence marginal costs increase.

Increased marginal costs can also be shown in an upward-sloping supply curve. This curve shows the relative cost of producing an extra unit of a given product and is therefore called the opportunity-cost curve or marginal-cost curve. Ignoring the fact that the slopes of the ppc are negative, this supply curve is basically the derivative of the ppc.

What production combination is chosen?

Competitive firms will produce a combination where the marginal costs equal the relative market price. If the opportunity cost of producing one product is lower than its relative market price, resources are reallocated and used to increase production of that product. When opportunity costs of a product are higher than its relative market price, it is profitable to decrease production of that product. Shifting resources like this will continue until the marginal or opportunity cost equals the relative price; hence when the slope of the ppc is equal to the relative price.

How do we depict the determinants of demand for two products simultaneously?

Consumers have various combinations of products they can consume that will give them the same level of well-being. These combinations can be graphically shown using indifference curves. Up and to the right of an indifference curve is better as it means consuming more of at least one product. While people can have infinite indifference curves, their actual consumption depends on their budget constraint or income:

Y = P1 x Q1 + P2 x Q2

For given income and prices, we can rearrange this formula to one that represents the quantity of a product that an individual is able to purchase:

Q1 = (Y/P1) - (P2/P1) x Q2

The slope of this budget constraint equals the negative of the price ratio P2/P1 or the relative price of the second product. Therefore, we call this budget constraint the price line as well.

Consumption is likely to happen where the indifference curve (what highest feasible combinations do I want to buy?) is tangent to the price line (what highest feasible combinations can I buy?).

How do we bring production capabilities and consumption preferences together?

To analyze consumption in an international context, we need more than individual indifference curves. We will utilize community indifference curves which show how the consumption of a group determines its well-being. First, it should be noted that analyzing the group as a whole overlooks the different preferences individuals have (different shapes of indifference curves). Second, while the group as a whole might be better of, it is likely that certain individuals will be worse off. Subjective weights of these gains and losses are not incorporated.

Without trade, the best an economy can do is to move to the production point where the domestic community indifference curve touches the production-possibility curve.

With trade, consumption beyond the domestic production possibilities is possible (graphically up and/or to the right of the ppc). Differences in price ratios are crucial for trade to be benefical. Opening up to trade will change the following:

- Countries will have import demand for the product with the low relative foreign price and export supply of the product with the high relative foreign price.

- Resources are reallocated and production will move along the production-possibility curve to the point where import demand equals export supply.

- Trade results in an equilibrium world price that falls within the range of the domestic relative prices in both countries.

- Consumption will be at the point where the new price line (representing the relative price) touches the highest community indifference curve.

Note that without trade, the optimal point is where the production-possibility curve, the price line and the community indifference curve all touch each other. Simply put, production equals consumption. With trade, this will not be the case as trade allows for consumption above and beyond the domestic ppc. The slope of these curves will still be the same at the optimal point as the relative price determines both production and consumption! With trade, however, domestic production does not need to equal domestic consumption as there will be a free-trade equilibrium. Therefore, there are two separate optimal points, one for production and one for consumption, which both touch the (relative) price line. We can use these optimal points to show the quantities of export and import for that country, as follows:

- Draw a line between these optimal points (note that this will be part of the world relative price line)

- Draw a vertical line through the point where the world price line is tangent to the domestic ppc

- Draw a horizontal line through the point where the world price line is tangent to the highest indifference curve

The result is a trade triangle that can be drawn for each country. When these triangles are the same size, the countries agree on the amounts traded and international equilibrium is achieved.

The ppc and indifference curves can be used to derive demand and supply curves. Given two relative prices (it is best to use the domestic relative price and the world relative price), look where the (relative) price lines touch the ppc to derive two points of the supply curve and look where the price lines touch the highest indifference curves to derive two points of the demand curve. These curves will cross at the equilibrium domestic relative price. At the world relative price, the difference between demand and supply will represent the import demand (if demand exceeds supply) or export supply (if supply exceeds demand). To see how the production possibility and indifference curves relate to the supply and demand framework, see figure 4.

What are the gains from trade?

As stated before, we assumed that an overall increase in consumption is a good thing and that losses by certain individuals do not outweigh the gains of others. The gains from trade are derived from the terms of trade, which is the price of a country's export product relative to the price of its import product. Logically, a higher world relative price of your export product improves your terms of trade.

What are the effects on production and consumption?

Production shifts toward the product in which a country has a comparative advantage/is more productive. More efficient world production is the result. Consumption of the importable product increases as the relative price decreases. Real income rises due to the improved terms of trade. Initially, consumption of the exportable product decreases since its price goes up. However, higher income might offset this effect.

What determines the trade pattern?

Recall that a difference in relative product price is crucial for trade to be beneficial. Prices can differ due to:

- Different production conditions. A difference can exist in resource productivities, availability of factor resources and the use of factors of production.

- Different demand conditions. Consumers across the world are likely to have different preferences.

- A combination of different production and demand conditions.

What does the Heckscher-Ohlin (H-O) theory teach us?

According to the Heckscher-Ohlin theory, product prices differ between countries because they use different factor proportions in production. A country is considered relatively labor-abundant if it has a higher ratio of labor to other factors than other countries. A product is considered relatively labor-intensive if labor costs are a greater portion of a product relative to other products. Abundance of labor is likely to lower labor costs and boost production of labor-intensive products like cloth in terms of quantity and efficiency. Cloth is therefore likely to be the exportable product with international trade. Scarcity of labor indicates higher labor costs and production of cloth is likely to be lower and less efficient. Hence, cloth would likely to be imported. Remember that it is the relative abundance of the factor of production that matters.

In the previous chapter, constant marginal opportunity costs were assumed. Since resources are scarce, it is more realistic to incorporate increasing marginal costs of production. This will be the main focus of this chapter.

This chapter will extend the examination of the effects of trade with income distribution and a distinction between the short run and long run effects.

Who gains and who loses within a country?

Short-run effects of opening trade

In the short run, factors of production cannot be easily transferred across industries. Following the theories outlined in previous chapters, factors used in sectors that are expanding (due to foreign demand) are likely to be valued more. Rents and wages are expected to increase. Factors used in sectors that are contracting lose income because the reduction in demand lowers their value.

The long-run factor-price response

In the long run, opposite effects will occur when factors will move from the contracting to the expanding sector. However, these will not offset the effects in the short run. Why not? The intensively used factors in the contracting market that are laid off are of limited use in the expanding sector. At the same time, the availability of the factors that are widely used in the expanding sector (and which are highly demanded) is limited. Production processes in the expanding sector need to adjust to the available resources in order to stabilize rents and wages. Nevertheless, people initially involved in the expanding sector will be absolutely better off in the end while people initially involved in the contracting sector will be worse off.

For example, if a country opening trade starts to export wheat and import cloth, the following happens:

- The price of wheat increases and the price of cloth decreases.

- More wheat and less cloth is produced in response to changed product prices.

- Excess supply of labor (laid off in the contracting labor-intensive cloth market) lowers wage rates as wheat production requires few workers.

- Land rents rise as wheat production requires a lot of land but little land becomes available in the contracting cloth market.

What are the three implications of the Heckscher-Ohlin theory for factor incomes?

The Stolper-Samuelson theorem

As shown, opening to trade has specific gainers and losers. The Stolper-Samuelson theorem can be used to show how real factor returns change in the long run. Free trade changes product prices which have to be equal to their marginal cost under competition:

Pwheat = Marginal cost of wheat = ar + bw

Pcloth = Marginal cost of cloth = cr + dw

r is the rental rate of land, w is the wage rate of labor, and a, b, c and d are input/output ratios indicating how much of that factor is needed to produce one unit of that good. Suppose that the input/output ratios remain constant, that the price of wheat increases by 10% and that the price of cloth stays the same. As the production of wheat requires mostly land, the rental rate r is likely to increase. Considering the second equation above, if the price of cloth stays the same, the wage rate w should fall. This makes sense because the cloth market contracts. Considering the first equation, a fall in wage rate would mean that the rental rate should increase by more than 10% to equal the 10% rise in the price of wheat. What this shows is that the market reward (r in this case) for the factor used intensively in the expanding sector, rises faster than the product price does. Purchasing power for this factor increases for both products, raising the real return for this factor (land in this case) in the long run. Similarly, the real return for the factor used intensively in the contracting market falls.

The specialized-factor pattern

The specialized-factor pattern entails that a factor gains more when it is specialized more in the production of the exportable product. This applies to the short run where the product price rises as well as to the long run where it still benefits from being used in producing the exportable product. Similarly, a factor loses more when it is concentrated more in the production of the imported product.

The factor-price equalization theorem

The factor-price equalization theorem states that free trade equalizes individual factor prices between the two countries under the following assumptions:

- Free trade equalizes the product prices in the two countries (as shown before)

- Production technologies are the same

- Both countries produce both products

- The same factors of production are used (equally skilled workers and land of comparable quality)

The theorem basically stresses that the goods are products of its factor inputs. So even when factors cannot be transferred across countries, they are reflected in the product prices. Shipping land-intensive wheat and labor-intensive cloth moves product prices and factor prices toward an equilibrium price.

Does the Heckscher-Ohline theory apply to practice?

Testing the H-O theory using the simple two-factor trade model failed to confirm the theory. Leontief was able to test the theory by assuming that the U.S. economy was capital-abundant and labor-scarce relative to the rest of the world. Using U.S. data, he found that the U.S. was actually exporting relatively labor-intensive products and importing relatively capital-intensive products. This finding that the world's most capital-abundant country had a lower capital/labor export ratio than import ratio is called the Leontief Paradox.

Should we abandon the H-O theory? No. Follow-up studies have shown the importance of making a distinction within the factors of production. For example, labor could be highy skilled, medium skilled or unskilled. Studies have shown that the U.S., being abundant in highly skilled labor, was indeed a net exporter of products that use highly skilled labor intensively, as predicted by the H-O theory.

Several patterns arise when we examine the relative abundance and scarcity of factors of production. Industrialized countries tend to be abundant in highly skilled labor and nonhuman capital whereas unskilled labor is relatively scarce there. Developing countries show opposite patterns. The presence of these different factors of productions is what we call factor endowments.

Another way to validate the H-O theory is to examine the distribution of factors in the patterns of trade of specific products. It is expected that this distribition will be unequal in the sense that a country exports products merely produced using its abundant factors. International trade patterns are quite consistent with the H-O theory although there are some exceptions.

In addition, the H-O theory proposed that factor prices would equalize when countries open up to trade. This proposal is based on some strong assumptions which are not all valid in the real world. When we examine factor returns, we do see the tendency toward equalization but full factor-price equalization does not seem to exist in the real world.

This chapter will extend the examination of the effects of trade with income distribution and a distinction between the short run and long run effects.

The theory of comparative advantage suggests that countries that are similar should trade little and that countries export some products while importing others. However, industrialized countries do trade a lot with each other and they do so with very similar products as well. This chapter looks beyond the standard theory of comparative advantage and examines scale economies and deviations from perfect competition.

What are scale economies?

Scale economies are basically increasing returns te scale. Up to know, we assumed constant returns to scale which means that the total cost of input use rises in the same proportion as output quantity and average cost is constant. With scale economies, output increases more than total cost and average cost falls. It is assumed that all long-run adjustments of factor inputs can and will be made, and factor (input) prices are constant. Increasing returns to scale are not constant or it would be infinitely benefical to produce more and more. Therefore, the average cost curve is a bowed inward curve when cost per unit is compared to the output quantity.

What is the difference between internal and external scale economies?

When scale economies arise from a firm's own decisions, they are internal scale economies. Examples are fixed costs or investments that are spread over more units of output and more efficient use of equipment that can operate at high volume. These scale economies can enable firms to move away from perfect competition. When there are some scale economies but a large number of firms is able to compete, there is monopolistic competition where products are differentiated and offered at slightly different prices. Larger scale economies can result in few firms competing or an oligopoly. This is expected to be more profitable as firms have more control over product prices. External scale economies depend on the industry. Firms can benefit from clustering (knowledge exchange, spillover effects) as it might attract more business to the region.

What characterizes intra-industry trade?

There is inter-industry trade, exporting and importing different products, and intra-industry trade (IIT), exporting and importing similar (industry) products. The difference between export and import of a particular product is called net trade. Net trade and IIT are both components of total trade. The latter can be measured as twice the value of the smaller of exports or imports, or as the difference between total trade and net trade:

IIT = (X + M) - |X - M|

The relative importance of IIT as a share of total trade can then be calculated as:

IIT share = IIT / Total trade = [(X + M) - |X - M|] / (X + M) = 1 - |X - M| / (X + M)

Intra-industry trade tends to be more important for manufactured products than for primary products like agricultural products. To examine how important IIT actually is, the sector is divided into numerous different products for which the IIT share is calculated separately. The weighted average that can be calculated gives some insights. IIT is more prevalent without trade barriers or significant transportation costs and it is more important for high-income industrialized countries.

What drives intra-industry trade?

IIT is driven by:

- Comparative advantage: product categories used to calculate IIT might consist of different products produced by different methods.

- Seasonal differences: two-way trade of similar products can reflect seasonal circumstances.

- Product differentiation: similar products, especially from different countries, are not always considered perfect substitutes.

How does monopolistic competition change our analysis of international trade?

Since perfect competition assumes homogeneous products, with product differentiation and scale economies we move to imperfect competition. Monopolistic competition is characterized by differentiated products, some power for producers in determining prices, internal scale economies, and easy entry and exit of the market in the long run (which arrives rather quickly).

The market with no trade

Differentiated products mean more substitutes for consumers. The more products or models available in the market, the lower their price. The reverse is true for the unit costs of production. Offering more models forces each firm to produce at a smaller scale, driving scale economies in reverse and increasing average cost. The very competitive nature of the market should equal prices with unit or average cost. We say that zero economic profit will be made in the long run.

Opening to free trade

Since some consumers in both countries are likely to prefer the foreign models, opening up to trade (IIT) integrates both markets. Consumers can choose between more differentiated products and the world equilibrium price will be lower than each of the countries' domestic price without trade. Following the scale economies in reverse, unit costs are likely to increase.

Basis for trade

Products become exportable when foreign market consumers demand unique models that your country produces. Similarly, domestic consumers demand unique foreign models making these products importable. Therefore, the basis for trade is product differentiation. Scale economies only play a supporting role. Firms can compete by offering different models but the analysis of scale economies and average cost shows that scale economies actually encourage production specialization.

Gains from trade

Without an extensive analysis, a major gain is that consumers can choose from a much greater variety of products for a more competitive (lower) price. Consumer well-being increases. In addition, domestic distribution of factor income and total output do not change much. This is because the amount of exports and imports and their respective factor inputs are not that different (differing capabilities, same industry). This characterizes intra-industry trade. Even if annual income falls for some groups, they will be better off if the greater variety of products offsets these losses. Finally, trade could 'benefit' an economy as a whole when the increased competition drives firms with higher costs out of business.

How does oligopoly change our analysis of international trade?

An oligopoly is characterized as an industry with few firms competing and accounting for most of total production. If these firms can avoid aggressive competition amongst them, they can set their prices high. Market entry becomes very attractive but is usually prevented by the substantial internal scale economies of existing firms in the market. However, setting a high price enables a competing firm to take business away by setting a somewhat lower price. Aggressive competition on prices could result while all firms in an oligopoly would be better off by not competing aggressively (on prices). This is what is called the prisoners' dilemma. The firms can opt for cooperating but they would still have an incentive to cheat because substantial economic profits can be earned by doing so, especially in the short run. An oligopoly might not seem beneficial for an economy as a whole, countries are likely to welcome an oligopolistic firm. Why? Because high export prices improve the terms of trade and a countries' national income increases by amounts that would have been part of foreign consumers' surplus.

How do external scale economies change our analysis of international trade?

External scale economies result from knowledge spillovers enabled by clustering. Expansion of the industry can benefit all firms in that region as it lowers production costs (remember that scale economies lower average costs as output increases). Initially, opening up to trade increases demand (demand curve shifts to the right) and raises output in turn to meet the new demand. Prices are likely to increase. However, additional external economies raise productivity and shift the supply curve to the right. Output increases and average costs decline. The new long-run equilibrium has a lower market price which has positive welfare effects for consumers in all countries. Producers of the exportable product tend to gain from increased industry output but the decrease in price mitigates this effect. The positive welfare effects for consumers in all countries contrast the analysis of a market with constant returns to scale. The main difference is that the new equilibrium price is lower for all consumers instead of consumers of the importable product only.

The theory of comparative advantage suggests that countries that are similar should trade little and that countries export some products while importing others. However, industrialized countries do trade a lot with each other and they do so with very similar products as well. This chapter looks beyond the standard theory of comparative advantage and examines scale economies and deviations from perfect competition.

The Heckscher-Ohlin theory looks at the international economy at one point in time. We have extended this view by shifting toward a free-trade situation. This chapter will focus on changes in productive capabilities or economic growth. Long-run economic growth can result from increases in the endowments of a country's production factors and from improvements in production technologies.

What is the difference between balanced growth and biased growth?

A country's production capabilities are reflected in its production-possibility curve (ppc). Economic growth shifts the ppc outward. When factor endowments increase proportionally or when technology improves by similar magnitude, we call it balanced growth. Expansion in favor of one of the products is called biased growth. If the relative product price stays the same, output changes disproportionately. It could be that economic growth enhances production of both products (continuing the two-product example) but this does not need to be the case. When the increased endowment or improved technology is not used in producing a product, its production will not increase. Its potential output given the ppc (the intersection with its axis) does not change and only the rest of the ppc shifts out.

Growth in only one factor is explained by the Rybczynski theorem which assumes constant product prices. Recall the two-product situation with wheat using land intensively and labor-intensive cloth production. If labor endowment grows, the ppc shifts outward with a bias toward cloth. Since labor is the more important factor in cloth production, cloth production increases. Wheat production could increase but won't. This is because cloth production also requires some land which has to be obtained from the wheat sector. The wheat sector will also lay off workers who can be reemployed to produce even more cloth. Therefore, the cloth sector will grow by more than the initial labor endowment growth and the wheat sector will decline. Output increases for the product using the growing factor intensively and decreases for the other product. To see how biased growth toward cloth changes production, see figure 5.

How does economic growth affect a country's willingness to trade?

Changes in a country's willingness to trade are reflected by a change in the size of the trade triangle. Remember that the trade triangle connects the point where the world price line is tangent to the domestic ppc (supply) and the point where the world price line is tangent to the highest indifference curve (demand). It summarizes how much a country wants to export and import.

Suppose that a proportionate expansion of production takes place. Again, we assume that the relative price remains constant. Given the proportionate expansion, the (relative) price line shifts outward. Income increases as well as consumption of both products. What happens to the willingness to trade? This depends on consumer preferences or the indifference curves as these determine the magnitude of the change in consumption. If consumption of the exportable product increases less than its production, the quantity available for exports increases. Hence, the willingness to trade increases. If consumption increases more than production, exports will decrease as shown by the smaller trade triangle and the willingness to trade decreases (try to picture this using the ppc, indifference curves and price lines). For the importable product, the willingness to trade increases when consumption increases more than production and decreases when consumption increases less than production.

If economic growth is sufficiently biased toward the importable product, production might rise by so much compared to consumption that it becomes an exportable product. In this case, the pattern of trade reverses itself as comparative advantage changes.

How does economic growth affect a country's terms of trade?

Recall that a country's terms of trade are the price of its exportable product(s) relative to the price of its importable product(s). A small country (in terms of its share in the world economy and its ability to influence the world price) has to take the world price as given but can benefit fom growth with increased consumption (reaching a higher community indifference curve). A large country is able to influence the world price and thus its terms of trade.

Consider the case where there is biased growth toward the importable product. Production of the importable product rises more than its consumption. Part of important demand will be met by domestic production, so fewer imports are demanded. Growth and higher income enable consumption of the exportable product to increase more than its production (if production rises at all; recall that this depends on the growth and use of particular factor inputs). Fewer exports will be supplied to meet domestic demand. These effects reduce a country's willingness to trade at any given price. So far, the relative price and the terms of trade are unchanged. However, the country could reduce import demand (lowering the relative price of the imported product) or reduce export supply (increasing the relative price of the exported product). This way, the country not only benefits from increase production possibilities but improves its terms of trade as the price of its exports relative to the price of its imports increases.

When growth increases the willingness to trade, increasing import demand increases the relative price of the imported product. Increasing export supply decreases the relative price of the exported product. These effects would hurt a country's terms of trade and it depends on the magnitude of change whether this offsets the initial growth in production.

Immiserizing growth

A very rare case is the one of immiserizing growth which means that increasing willingness to trade (by growth and expansion) makes a country worse off by reducing its terms of trade. How does this work? The following conditions need to be met:

- Growth must be strongly biased toward the exported product increasing willingness to trade of a large country.

- Foreign demand must be price inelastic to establish a large drop in the world price as a result of the country's increased export supply.

- There have to be decent terms of trade to start with, so that the drop in terms of trade is large enough to offset the initial growth in production.

You might wonder why a country would increase export supply or import demand in this case of harmful trade. It's simply because these decisions are made by competitive firms of which some are likely to be better off in the end. This has some important implications for national policy though. A government might want to improve its country's terms of trade by favoring import-replacing industries over export industries.

Dutch disease

A second problem caused by developing a new exportable natural resource is called Dutch disease. The Netherlands started to use new natural gas fields what depressed the manufacturing industy. The Rybczynski theorem helps to illustrate this effect in two ways. First, the natural gas production drew resources away from manufacturing. Both labor and capital moved away from manufacturing, causing this sector to contract. Second, foreign money moved into the Netherlands to profit from the natural gas production, causing the Dutch currency to appreciate. Manufacturing firms had a hard time competing with foreign firms whose prices became relatively lower. The resulting drop in demand caused the manufacturing sector to contract.

How do improvements in production technologies affect trade?

A country tends to produce products in which it has the relatively better technology. This source of comparative advantage can influence the pattern of trade. This would offer an alternative explanation to the Heckscher-Ohlin theory which incorporates the relative abundance of factor inputs. However, we could argue that technological improvements result from the relative abundance of high-skilled labor and venture capital organized in research and development (R&D). It is not clear what happens to the country in which the technology is developed because technologies can be easily spread internationally. We call this diffusion.

To help us find a pattern in the development and diffusion of technologies, we use the product cycle hypothesis. Invention and development of a new technology requires R&D, (trial) production and marketing, all of which are likely to be present in advanced developed countries. Once the production technology becomes more standardized, factor intensity might shift to less-skilled labor. Production might move to countries that are relatively abundant in less-skilled labor. The product cycle hypothesis does seem to be applicable to practice despite some limitations. First, the length and progression of the phases of the cycle are unpredictable. Second, diffusion often occurs within multinational corporations causing the cycle to basically disappear.

How does openness to trade affect growth?

We have shown the impact of growth on international trade. Several explanations exist to prove that it works the other way around as well:

- Closing yourself to trade makes you lose out on adopting and using new technologies developed in other countries.

- Competitive pressure increases, enhancing the incentive to innovate.

- Firms might earn higher returns on innovation in foreign countries (again, enhancing the incentive to innovate).

- Absorbing new technologies enables developing additional innovations.

Testing these ideas in practice shows evidence of a positive relationship. However, proving the direction of causation and excluding other effects remains a challenge.

The Heckscher-Ohlin theory looks at the international economy at one point in time. We have extended this view by shifting toward a free-trade situation. This chapter will focus on changes in productive capabilities or economic growth. Long-run economic growth can result from increases in the endowments of a country's production factors and from improvements in production technologies.

Previous chapters have shown the economic benefits of opening up to trade. This chapter examines what is lost or gained by imposing trade barriers like a tariff. This tax on imported products can be a monetary amount per unit, called a specific tariff, or a percentage of the estimated market value of the product at the moment of arrival, called an ad valorem tariff.

Tariff rates are generally imposed to protect a country but have been declining over the years. A key role in this can be assigned to the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), now part of the World Trade Organization (WTO). The aim of the WTO is to establish lower, non-discriminating and fair tariffs. It has been successful mostly for developed countries. Developing countries were often left out of negotiations as they did not trade that much. Recently, developing countries have been included and tariffs have been reduced even more. However, tariffs are still very present today so it is important to explore their pros and cons in more detail.

What are the effects of a tariff on domestic producers and consumers?

It is very intuitive to say that an import tax benefits domestic producers as it raises the price of the imported product. Domestic producers can either expand production, raise their price, or do both. We can illustrate this by using the common demand and supply framework. Consider a small country where firms have to take the world market price as given. Recall that import demand results from a world price below the domestic equilibrium price. In addition, recall that there is less producer surplus in this free-trade situation and more consumer surplus compared to a no-trade situation. As we consider a small country, any tariff on imports is likely to be passed on directly to consumers (by an increase in price). Domestic producers can raise their prices by the same amount if their products are (close) substitutes. Domestic supply increases, domestic demand decreases, and import demand decreases as a result of the new domestic price with a tariff. Extra surplus on the products already sold and additional sales both increase producer surplus. Consumers are worse off. Less surplus on the products already bought and fewer purchases both decrease consumer surplus.

The net effect for the country seems clear. Since this tariff is imposed on an imported good, domestic demand outweighed domestic supply. Domestic producers gain on domestic output while domestic consumers lose on both domestic and foreign output. The tariff is a net loss in the market.

It is important, however, to take the government revenue from the tariff into account. This revenue is equal to the new amount of import times the monetary value of the tariff. The government could use this to compensate losses (by cutting taxes for example), spend it on other projects or consider it extra income.

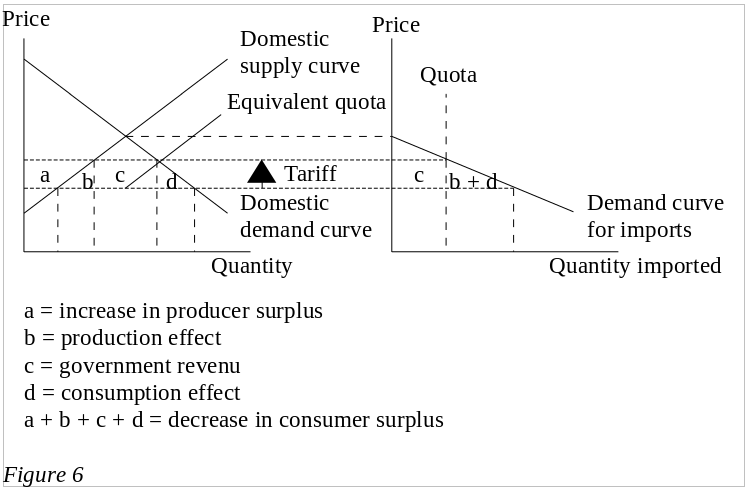

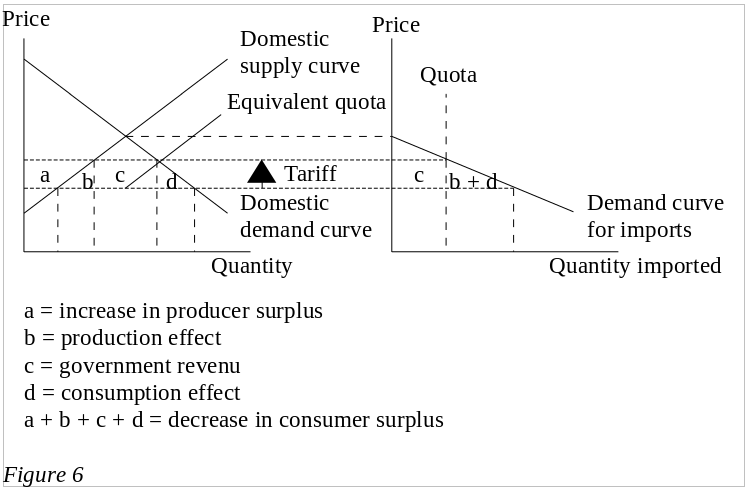

What is the net national result from a tariff?

As illustrated in chapter 2, we can use the one-dollar, one-vote metric as a social value judgment. Every dollar of gain or loss is considered equal by this metric. The net result can be shown by deriving an import demand curve from the domestic supply and demand framework and its price lines. Starting with the domestic equilibrium price where import demand is zero, import demand (the difference between domestic demand and supply) increases for each price below the domestic equilibrium price. From this, a downward sloping import demand curve can be drawn. If we add both the world price line and the domestic price line with a tariff, and draw two vertical lines to the horizontal axis from the points where the price lines touch the import demand curve, two areas arise. The rectangle is the government revenue which can be calculated by the amount of imports times the monetary value of the tariff. The triangle is the net national loss from imposing the tariff. Part of this is called the consumption effect. It is the loss due to reduced consumption in response to the higher price. As it is a loss in consumption, neither producers nor the government gains here, so this is called a deadweight loss. The other part of the net national loss is called the production effect. Producers experience increasing marginal costs as they shift resources from importing to domestic production. These extra costs are paid for by consumers but neither the government nor the producers gain here, so this is a deadweight loss as well. To see the net net national loss from a tariff (or its equivalent quota), see figure 6.

What is the effective rate of protection?

The effect of a tariff can be expressed in terms of value added which is the amount used to pay for the primary production factors in an industry. It is common that many tariffs are imposed, not only on products. Tariffs on importable products usually help domestic producers. Tariffs on inputs generally hurt domestic producers. The net result is the effective rate of protection which measures by which a nation's full set of trade barriers raises the value added per unit of output. The nominal rate of protection is the tariff paid by consumers on the output. When this tariff rate on output is higher than the one on its inputs, the effective rate of protection will be greater then the nominal rate.

What about export taxes?

The effects of an export tax are very similar to the effects of an import tax. A large country with monopoly power in the world market could use tax exports to increase the world price and earn higher returns on its exports. Other reasons to impose export taxes are raising government revenue or favoring domestic consumers.

How can monopsony power be used to affect trade?

Individual firms might not be able to affect the price at which foreigners supply imports. If a nation collectively is able to do this, it is considered a large country that has monopsony power which it can use to improve its terms of trade (price of exports relative to price of imports). Since we consider a large country, the foreign export supply curve is upward sloping. In a small country case, it would have been flat. Foreign export supply would be infinitely elastic with the fixed world price, and the terms of trade could not be changed. A large country imposing a small tariff has the following effects:

- Import demand decreases as the domestic price increases.

- Foreigners can export fewer products and will produce less.

- Decreased production lowers foreigners marginal cost.

- Foreigners will compete by lowering their export prices.

Who gains and who loses? Domestic consumers pay a higher price with the tariff so their consumer surplus decreases. The special nature of this large country case is that foreign exporters also pay part of the tariff by lowering their export prices. The government receives revenue equal to the imported quantity times the tariff. The country imposing the tariff still experiences a deadweight loss. Part of this is due to decreased consumption; some consumers are willing to pay more than the foreigners export price but won't pay the higher domestic price including the tariff. The other part is the deadweight loss from the production effect as it is inefficient for domestic firms to move resources from importing to domestic production. Nevertheless, their producer surplus increases. The domestic deadweight loss will be outweighed by the part of the tariff that is absorbed by foreign exporters. The country imposing the small tariff is better off while the world as a whole is worse off. This will be the case for all tariffs up to a prohibitive tariff. Here, foreign exporters decide not to export at all to the country imposing the tariff and all gains from international trade are lost.

Assuming the world does not respond to the imposed tariff, there is a nationally optimal tariff where the country imposing the tariff has the largest net gain. For this country, it is best when the drop in foreigners supply is as small as possible (enabling more exploitation), so when their supply is more inelastic. This implies that the optimal tariff rate is equal to the reciprocal of the price elasticity of foreigners relevant export supply.

Previous chapters have shown the economic benefits of opening up to trade. This chapter examines what is lost or gained by imposing trade barriers like a tariff. This tax on imported products can be a monetary amount per unit, called a specific tariff, or a percentage of the estimated market value of the product at the moment of arrival, called an ad valorem tariff.

Tariff rates are generally imposed to protect a country but have been declining over the years. A key role in this can be assigned to the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), now part of the World Trade Organization (WTO). The aim of the WTO is to establish lower, non-discriminating and fair tariffs. It has been successful mostly for developed countries. Developing countries were often left out of negotiations as they did not trade that much. Recently, developing countries have been included and tariffs have been reduced even more. However, tariffs are still very present today so it is important to explore their pros and cons in more detail.

Next to imposing a tariff on imports, a government can use a nontariff barrier (NTB) to reduce imports. An NTB can limit the quantity of imports directly or indirectly by raising the costs of importing. This chapter will consider several NTBs of both types and their effects in the marketplace.

How does an import quota work?

An import quota or quota limits the imported quantity directly. Imports beyond a certain quantity are not allowed, so it has an impact if more products would be imported without the quota. A quota might be favored over a tariff as a tariff allows for imports to rise. It can be a powerful tool for government officials as well, as they might decide who gets the import licenses.

What differs a quota from a tariff for a small country?

Setting a quota limiting imports to a smaller quantity then with free trade leaves the domestic market with excess demand and a shortage of supply. The domestic price increases until import demand is equal to the quota. Recall that a small country does not affect the world price in this case. These effects are similar to imposing a tariff rate that reduces import demand to the same quantity as the quota here. Figure 6 shows how an equilavent quota shifts the domestic supply curve to the right and causes the same effects as the tariff. From the above reasoning, it is clear that:

- Domestic production and product price increase, so producers are better off.

- The fall in consumption and increased price lower consumers surplus.

- The country loses some income as producers face increased marginal costs (up to the new price) whereas it would be cheaper to import them from foreign exporters at the free-trade equilibrium price (the deadweight loss triangle with the production effect).

- Part of the fall in consumption and consumer surplus is not gained by anyone else (the deadweight loss triangle with the consumption effect).

A crucial exception is the area that would have been government revenue in case of a tariff. This area is the total of markups that result from imports at the world price and sales at the domestic price. What happens with these markups depends on the distribution of the import licenses. They can be allocated in different ways, each having their own implications:

- Fixed favoritism: licenses are allocated to importers without any resource costs. This way, domestic producers are better off by what domestic consumers are worse off. A political reason to allocate them proportionally to already existing importers is that they might lobby to block the entire quota otherwise. Their quantity of imports declines but average returns will be higher.

- Auction: an import license auction allocates the licenses to the highest bidders. Their offer is likely to be very close to the markup (or else they would be outbid) which directs nearly all revenues to the government. Corrupt government officials could take bribes to allocate the licenses differently but this would incur additional (social) costs beyond economic market inefficiency.

- Resource-using procedures; a resource-using application procedure encourages firms to invest heavily (up to the markup) in order to receive business. Since a lot of firms could be willing to invest under the assumption that it brings them business, a lot of resources could be wasted. This quota inefficiency makes the quota worse than the equivalent tariff when it comes to national well-being.

What differs a quota from a tariff for a large country?

A similar pattern arises compared to a small country. The effects of a quota are basically the same as for the equilavent tariff. The domestic price rises and the foreign export price declines until the difference is equal to the equivalent tariff and the import demand is equal to the quota. Again, the exception is the area that would have been government revenue in case of a tariff. Whether additional domestic gains can be made or whether the quota actually hurts the country depends on the resource costs associated with allocating the import quota licenses.

When the domestic industry is a monopoly, the difference between a quota and tariff can be quite substantial. The domestic producer would lose surplus if it sets its price higher than the foreign (world) price including the tariff. Consumers will demand more imports. In case of a quota, however, imports are limited and the monopolist can exert its monopoly pricing power. This way, or when the distribution of quota licenses wastes resources, the import quota is worse than the tariff for the country as a whole. Nevertheless, it is clear that the domestic monopoly prefers the quota.

How do voluntary export restraints work?

A voluntary export restraint (VER) is a trade barrier where an exporting country agrees to limit its exports to the importing country. It restricts sales and raises prices. Importing countries can do this to protect domestic firms that have trouble competing internationally. The exporting country's government might want to benefit from the VER by selling export licenses. However, it is in the best interest of exporting firms if they refrain from competition and charge the highest price that consumers are willing to pay. Here, the difference with an import quota becomes clear. The markups on the price are not 'for sale' in the domestic market but go to foreign exporters instead. Note that this is an extra loss for the country imposing the barrier but not for the whole world. Two additional effects of a VER might occur. First, foreign exporters might shift production toward varieties with higher returns because the limit on exports changes the optimal mix of varieties. Second, the import protection might incentivize foreign firms to directly invest in the country. Foreign direct investment will be discussed in another chapter.

Which other nontariff barriers are commonly used?

- Product standards: government regulation can restrict the import of products that do not meet certain requirements. Meeting these requirements or testing and certification can be costly for foreign exporters. Product standards usually do not bring in revenue from tariffs or taxes. It actually requires the government to use resources in regulating product standards. A country could be better off if there are health, safety, environmental or other benefits involved.

- A domestic content requirement requires imports to have a minimum of domestic production value in terms of components or parts for example. A similar barrier is a mixing requirement where a certain percentage of the product must be produced by domestic producers. Again, there is no government revenue in terms of tariffs or taxes. The price markups are likely to go to domestic producers. This does generate the deadweight losses we have seen in previous chapters.

- Government procurement: governments can choose to refrain from buying imports and buy domestic products instead.

What are the costs of protection?

Graphically, the costs of protection were shown by the deadweight losses in chapter 8. As described, the net national loss depends on the tariff and the reduction in import demand. To illustrate whether the costs of protection are large or small, we calculate its relative importance to a nation's gross domestic product (GDP) as follows:

(Net national loss from the tariff / GDP) = 0.5 x Tariff rate x Percent reduction in import quantity x (Import value / GDP)

This formula can be used for nontariff barriers as well as it adds up the losses of all products from import protection. If the tariff is rather small and a country does not heavily rely on imports, losses will be limited. However, the following events would increase the costs significantly:

- Foreign retaliation: foreign countries imposing barriers harms the domestic country.

- Enforcement costs: labor and other resources are used to enforce the barrier and represents a waste as these costs are not gained by others.

- Rent-seeking costs: producers might incur costs seeking protection (e.g. lobbying) wasting surplus that was gained on consumers.

- Rents to foreign producers: in the case of voluntary export restraints, foreign exporters raise their prices harming the importing country.

- Innovation: protection lowers competitive pressure and consequently the incentive to innovate.

In addition, protection is likely to reduce the number of varieties of products available in the market harming national well-being as well. From this, it is clear that creating protected income is likely to incur significant costs, even for a small level of protection.

What global efforts have been made to eliminate barriers to trade?

The GATT and the WTO were quite successful in eliminating import quotas but countries increasingly use other NTBs. The Kennedy Round and Tokyo Round are multilateral trade negotiations of the GATT that led to some agreements regarding NTBs but the Uruguay Round was more successful. Here, more NTB codes applying to all WTO members were negotiated and phasing out VERs on textiles and clothing was one of them. The most recent is the Doha Round which is very promising but hasn't been successful yet.

Countries fighting over trade barriers have had numerous international trade disputes. About half of them have been successfully negotiated by the GATT. The U.S. thought the GATT's settlement procedures were too weak and enacted Section 301 giving their president the right to eliminate unfair trade practices by threatening with retaliation. Many countries opposed section 301 and the U.S. has reduced its use since the WTO improved international dispute settlement procedures. Threatening retaliation by the WTO is usually successful but actual retaliation would be problematic because the WTO is supposed to liberalize trade.

Next to imposing a tariff on imports, a government can use a nontariff barrier (NTB) to reduce imports. An NTB can limit the quantity of imports directly or indirectly by raising the costs of importing. This chapter will consider several NTBs of both types and their effects in the marketplace.

Previous chapters have shown that import barriers can increase domestic production (and employment), decrease domestic consumption, increase government revenue and change income distribution. There seem to be few situations in which a country is actually better off by imposing trade barriers. This chapter examines when import protection might be the best policy and what role politics play.

What characterizes an ideal world according to an economist?

In a first-best world the market is perfectly competitive. Free trade is economically efficient. Marginal costs to each group as well as to society as a whole are included and optimal at the equilibrium. This would mean that nobody could be better off without harming someone else more. Here, the market price not only equals the buyers' private marginal benefit (MB) and the sellers' private maginal cost (MC), but also social marginal benefit (SMB) and social marginal cost (SMC). Each deviation from this equilibrium would mobilize private producers or consumers to alter their level of production or consumption.

What characterizes a realistic world according to an economist?

In a second-best world the market has to deal with distortions. Private actions will not be efficient for society as a whole due to market failures or government intervention. Four market failures and their effects are:

- External costs: social marginal cost exceeds the price. An example of such an externality or spillover effect is pollution. Too much is supplied.

- External benefits: social marginal benefit exceeds the price. An example of such an externality is when too few workers are hired in the sector where knowledge from training or education spills over to people outside the sector. Not enough is demanded.

- Monopoly power: the price is set too high and supply is restricted. Not enough is demanded.

- Monopsony power: the price is too low; a firm dominating the labor market could set a low wage. Not enough is supplied.

In case none of these market failures exists, the government can distort the market by imposing a tax (e.g. a tariff where not enough is demanded) or subsidy. The latter is basically a negative tax lowering the price to buyers. In this case, too much is demanded.

How could government policy fix distortions caused by externalities?

Pigou developed the tax-or-subsidy approach whereas Ronald Coase developed the property-rights approach. The tax-or-subsidy approach is much more put into practice and will be discussed here. An externality where social marginal cost is too high should be fought by a tax that closes the gap between the social marginal cost and the private marginal cost. Similarly, when social marginal benefit is too high, a government subsidy would close the gap between the social marginal benefit and the private marginal benefit.

It should be noted that governments might fail to identify the problem or provide the solution. One of the causes could be that the analysis of a trade barrier is complicated when externalities or other distortions are involved. One way to deal with this is to apply the specificity rule. This rule states that a government intervention is usually more efficient if it directly tackles the source of the distortion.

How do a tariff and subsidy compare when domestic production is promoted?

Several reasons to protect domestic production or employment exist:

- Local production has positive effects that spillover to other groups;

- Additional employment requires new skills that benefit other areas of the economy when workers switch jobs;

- Additional production (at high cost) might enable producers to lower their costs over time;

- Without protection, extra costs arise when workers need to switch jobs to stay employed;

- Local production makes citizens proud;

- Local production is essential to national defense;

- Redistributing income can benefit the poor or disadvantaged groups in society.